Hi everyone. The following blog post is written by 2024 Hubbard Fellow Claire Morrical. Claire put together a fantastic series of interviews with people working in conservation here in Nebraska and we thought you’d enjoy reading and listening to their stories.

This project – Perspectives of the Prairie – uses interviews and maps to share the perspectives and stories of people, from ecologists to volunteers, on the prairie. You can check out the full project HERE.

This post also contains audio clips. You can find the text from this blog post with audio transcripts HERE. If you’re reading this post in your email and the audio clips don’t work, click on the title of the post to open it online.

Brandon joined TNC as a Hubbard Fellow. Through his fellow project, which was a summit with indigenous partners, Brandon created and filled an invaluable role as TNC Nebraska’s Indigenous Partnership Programs Manager. Brandon and I met to talk about how lessons about life and stewardship from the fellowship impact his work today, the summit and the relationships Brandon works to form today, and his hopes for the future of cultural fire.

Interview: October 24th, 2024

Part 1: Meet Brandon

Location: The Derr House (the main office) at Platte River Prairies

This is Brandon Cobb. Brandon is the Indigenous Partnerships Program Manager for the Nebraska Chapter of the Nature Conservancy. But before that, he was a 2022 Hubbard Fellow at Platter River Prairies. Hubbard Fellows spend the year immersed in all aspects of conservation. We work as land stewards, researchers, educators, fundraisers, and more.

Brandon and I chatted at a picnic table outside of Platte River Prairie’s main office, which sits on a small hill. From there we could look out over the surrounding acres of prairie. The gently rolling Derr Sandhills, recently re-fenced for grazing, the wetland, and the lowland beyond it. We manage the acres with great care but with the understanding that nature, in all its complexities, will take the reins when it wants to, and so we often give them up willingly. We mix and scatter seed without precision. Although confined to a unit, we watch fire burn what it will and accept what it leaves untouched.

Brandon reflects on this complexity, comparing historic prairies to those now under our care.

Part 2: Life Lessons from Tangled Fences

Location: The Studnicka site at Platte River Prairies

As a fellow, Brandon spent a significant amount of time at our site – Studnicka. Studnicka is a site with a lot of value, but also, it’s fair share of challenges. Studnicka houses two of our crane blinds where viewers can creep in before sunrise and watch the first light reveal thousands of cranes on the water, or watch cranes arrive on the river and disappear as the sun sets in the evening.

Unfortunately, as of 2024, Studnicka also houses a good deal of invasive grasses. But this presents us with the opportunity to get creative, and ask ourselves, “how can we remove invasive grasses and create an opportunity for more diverse prairie to grow here?”

Brandon’s story shares one approach we tried.

Notes for Context: Brandon talks about our use of grazing on prairies here. Many prairie preserves in the Great Plains use cattle grazing to mimic the role that bison have historically played on prairies. Cattle can be a great way to create disturbance and different structures across the prairie (such as areas of tall or short grass that favors different species) and, as Brandon mentions here, to manage invasive species. Learn more about grazing HERE.

- Riparian: the banks of a river or stream

- Cody Miller: the preserve manager at PRP

- Hotwire: electric fence, less sturdy than barbed wire fence, but easier to put up and take down

Brandon does much less stewardship work in his current role, but he’s thoughtful in the way that he carries these experiences with him. These lessons, philosophical and practical, are still relevant in Brandon’s position as the Indigenous Partnerships Program Manager.

Here is another story from Studnicka that continues to influence Brandon’s work.

Note for Context: Brandon mentions the independent project that he completed for the Hubbard Fellowship here. We’ll learn more about the project in “Listening to Tribal Partners“.

Part 3: Listening to Tribal Partners

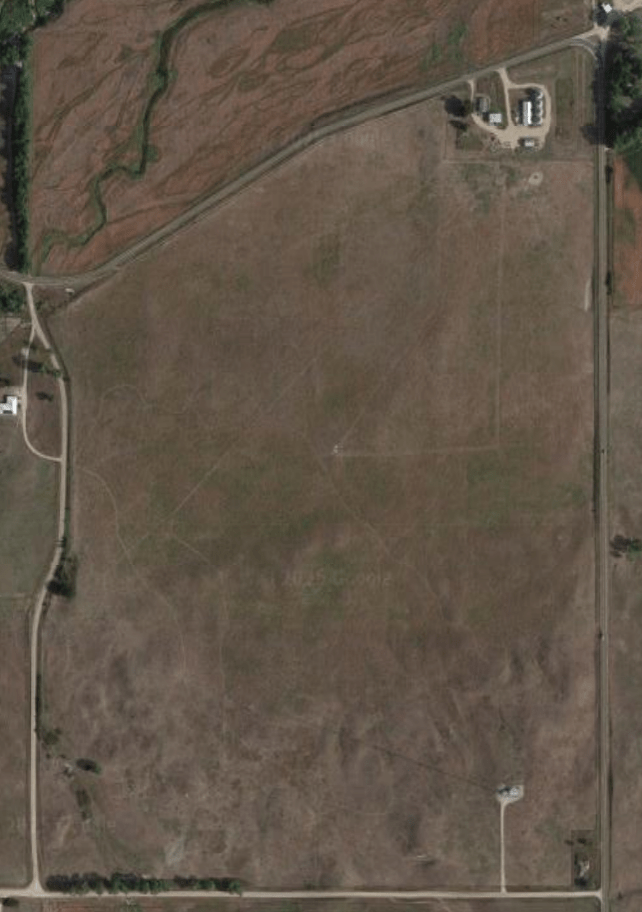

Location: Eastern Bison Pasture at Niobrara Valley Preserve

As part of the Hubbard Fellowship, each fellow completes an independent project of their choosing. Fellows have completed research projects, written educational comic books, and collected interviews into a project titled “Perspectives of the Prairie” … Anyway.

Brandon’s project began as an exploration of how to better collaborate with tribal partners which grew into a summit and eventually a full-time position.

As Brandon emphasizes, a key part of this summit was spotlighting tribe’s perspectives and objectives, with TNC operating primarily as a listener, rather than a speaker.

Brandon’s fellowship became a full-time position with the Nature Conservancy in Nebraska, as an Indigenous Partnerships Program Manager, where he prioritizes the interests of indigenous partners.

He continues to draw on what the lessons he learned as a fellow, both philosophical and practical.

Brandon shared an example of the grazing work he’s been doing with the Ponca tribe, and how both the Ponca and the Conservancy have learned and grown from this relationship. In reference to this story, and the stewardship, knowledge, and relationships that have come out of TNC Nebraska’s bison herd, the associated waypoint is located in the eastern bison pasture.

Notes for Context: Brandon mentions a shift away from cow-calf operations in bison ranching. In cow-calf operations, calves may be weaned pulled out of a herd the same year that they are born. This can put stress on bison calves and make it more difficult to introduce them to new herds. As I’ve heard a member of our staff say, “they haven’t learned how to be bison yet.”

- Niobrara: Niobrara Valley Preserve, located in the Nebraska Sandhills, is 56,000 acres and is home to the Nebraska Nature Conservancy’s two bison herds.

- PRP: Platte River Prairies

Part 4: Burning the Front Lawn

Location: The front yard of the Derr House (the main office) at Platte River Prairies

As part of the program, fellows participate in prescribed burns. They’re first introduced to fire on a few acres, learning to step boldly through it, monitor it, and watch its behavior as if it were a critter. Fellows spend the year burning on Platte River Prairies, Niobrara Valley Preserve, and with conservation partners in Nebraska. If they’re lucky, by the end of the year, they’ve burned hundreds, maybe thousands of acres. Here’s Brandon sharing the impact of his first burn with the Nature Conservancy.

Notes for Context: Brandon refers to the front yard, two-acre prairie in front of our headquarters surrounded by a gravel lane.

- Cody Miller: The Platte River Prairies preserve manager

- Drip Torch: A metal canister with a mix of gasoline and diesel fuel. Fuel runs through a long metal wick to the lit end, where it’s set on fire and falls to the ground, leaving a trail of flames behind the lighter.

Just as small lessons from the fellowship have grown with Brandon and his career, from the spark of a two-acre burn, Brandon has flourished in fire. His practical experience allows him to build partnerships to put fire on the ground and build community around fire. Brandon shares his experience with one such community, the Indigenous People’s Burning Network (IPBN), telling us about its importance to its participants and the future of fire.

The National Wildfire Coordinating Group (NWCG) is formed by a collective of governmental members such as the US Forest Service, and provides standards, practices, and trainings for fighting wildfire. However, these expectations are often extended to prescribed fire. NWCG standards and qualifications can be extensive and rigid, which makes sense when you’re trying to effectively coordinate and put out large or dangerous wildfires. They can be an excellent resource. But just as fire is complicated and variable across landscapes and conditions, so are approaches to prescribed burning. Brandon shares a perspective shifting conversation and talks more about what cultural fire looks like on the ground.

Notes for Context:

- Cultural Fire Management Council: Facilitates cultural fire with the Yurok People through projects like fire training programs

- Hand Line: A line or perimeter where hand tools, like rakes or hoes, are used to expose bare soil, preventing fire from spreading past it

Part 5: Cultural Surveys with Stacy Laravie

Location: The Niobrara River at Niobrara Valley Preserve

As is often the case, looking to the future means also considering the past. In cultural burns, this is relying on generational knowledge of a place to plan and execute the burn. At Niobrara Valley Preserve, this meant investigating the history of what the landscape meant to people and how they interacted with it to inform our perspective and our actions today.

Brandon was joined by TNC Nebraska’s newest board member, Stacy Laravie, in conducting surveys to identify culturally significant sites for tribes whose ancestors would have spent time on what is now NVP. Stacy is a member of the Ponca Tribe of Nebraska, with background as a Tribal Historic Preservation Officer for the Tribe. Her role includes finding, identifying, and interpreting sites such as these.

Notes for Context: You can learn more about discussions to dam the Niobrara HERE (“Amanda Hefner 4: No dam on the Niobrara”).