This post is written by Kate Nootenboom, whose Hubbard Fellowship is fast coming to a close. Her fellow Fellow, Sara Lueder, finished up this week and Kate will be leaving after next week. Shortly after that, our two new Fellows will be arriving (look forward to introductions soon!). Each Fellow works on an independent project while they’re here. Kate’s project included an exploration of soundscape ecology and the acoustics of prairies. I think you’ll agree it’s a fascinating topic! – Chris

How often do you go to a prairie, and close your eyes?

My guess is that most of us default to visuals when taking in a landscape. It makes sense – depending on the season, prairies can be vivid scenes of colorful blooms, shifting shades of earthen hues, or vast canvasses of winter white. This very blog is a testament to the joys of the optical, but today I’m here to humbly request we give one of the other senses a little time in the sun.

Over the course of this year, I’ve been tuning in, quite literally, to the prairie soundscape, as part of my independent project for the Hubbard Fellowship. A series of podcasts and TED Talks (link) piqued my interest in the field of soundscape ecology, and I’ve been exploring the potential of acoustic data as a tool for scientific inquiry, land management, and, of course, storytelling. I’ve summarized my findings here in the hopes that it will open your ears to an alternate and exciting way of communing with nature.

What is soundscape ecology?

Broadly speaking, soundscape ecology is the idea that the symphony of an ecosystem can reveal clues to its biodiversity and wellbeing. Often, sounds are partitioned into three discrete categories: biophony (sounds of the biotic world: birdsong, elk bugle), geophony (sounds of the abiotic world: rainfall, wind), and anthropophony (sounds of the man-made world: train whistles, sirens). The data can be analyzed to constrain certain indices like acoustic complexity, diversity, and evenness of an ecosystem, and to help identify the presence or absence of certain species.

In addition to their scientific potential, soundscapes are also just a beautiful, but often underrecognized, way to connect with nature. For those of us who hear, sound is an important tool for absorbing our surroundings, and we use it near constantly (whether consciously or not). If well-enough-acquainted, the sounds of a prairie can reveal clues to determine the season, the time of day, even the weather. The arrival of bobolinks’ self-declaratory song heralds the coming of summer in Nebraska, and the whispery rustle of dry cottonwood leaves can tell you it is autumn, and you are near water.

That likely isn’t revelatory information for the prairie enthusiasts here, but this might be: one of the truest and most unexpected joys in this process was unearthing the unfamiliar shapes of very familiar sounds. This discovery came from scrolling through spectrograms of audio files, which plot frequency (pitch or tone) against time, with variations in color representing amplitude (loudness). Spectrograms are, of course, human inventions, and I am once again delighted by the ingenuity of our species to capture and convey natural phenomena in ways both scientific and beautiful. If nothing else, I find it oddly mesmerizing simply to see sound.

Who knew the call of a demure American goldfinch could resemble the mighty scrape of grizzly bear claws in tree bark? Or that you can see the loping motion of a triumphant coyote pack in their sound signature? The spectrogram of a bobwhite quail even mimics music notation itself: a half rest followed by an eighth note.

Soundscape ecology as science

Individual audio moments, like those captured in the spectrograms above, are the poignant vignettes of a much larger story that can be told through sound. Accumulation of acoustic data over days, weeks, years, or decades will yield datasets that can be plumbed for a variety of information. Archiving the soundscape of a prairie as it exists now is a bit like entombing its residents in shale for future geologists to unearth; a “soundscape fossil record” can provide future ecologists with comprehensive information about who was here, and when.

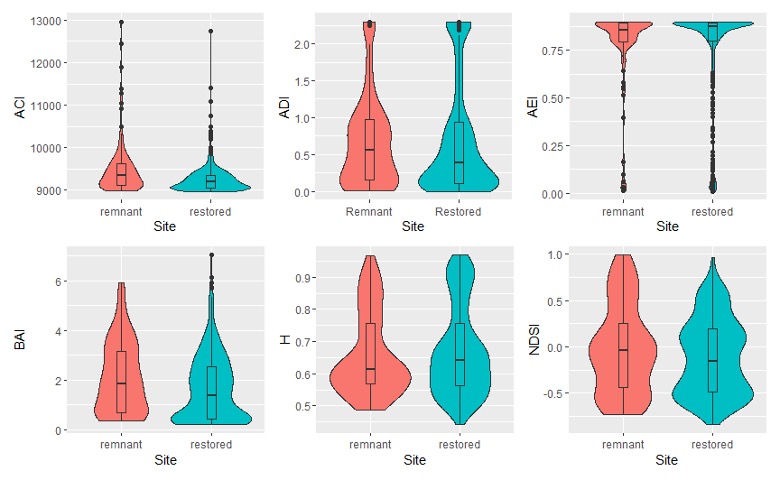

My foray into the scientific side of soundscapes focused on two adjacent patches of prairie near the Platte River, one a remnant and the other a restoration. I chose these units because they’ve been the subject of a multi-year study on small mammal presence, and I was interested in adding a layer of acoustic data to an existing comparative dataset. Curious to see if the soundscape changed dramatically between a remnant and a restoration, I set up devices in each unit and recorded the first five minutes of every hour for two-week intervals between August and November.

Once collected, I calculated six different indices from the data. A software program analyzed each five-minute clip and scored it on each of my selected indices. Acoustic Diversity Index, for example, describes how acoustically diverse the soundscape is on a seemingly arbitrary scale of 0.0 – 3.0. Below, I arranged the data into violin plots comparing audio from the remnant and the restoration for each index. I chose violin plots because a) other soundscape ecologists seem inclined to use them, and b) they are named after a musical instrument. And this project is about sound.

Encouragingly, the plots appear largely similar between the two, suggesting that habitat, as reflected by soundscape, does not differ drastically from remnant to restored. Deeper data analysis would reveal a more nuanced story, but hopefully this glimpse inspires curiosity for the kinds of scientific questions that can be asked and answered in this growing field.

Who else is using soundscapes?

I am far from alone in my enthusiasm for Great Plains soundscapes. Other scientists have looked at soundscapes and their effect on American burying beetle (Nicrophorous americanus) distribution, or the acoustic rebound in a prairie ecosystem following a prescribed burn (link). Still others have taken the storytelling approach by pairing soundscapes with time-lapse images to condense phenological phenomena into digestible dramas (link).

For land managers, acoustic monitoring has huge potential for measuring biodiversity across landscapes and through time, with far less intrusion into an ecosystem than other strategies. Monitoring can take many different forms and is often best tailored to the objectives in mind, so acoustics are not a perfect replacement for existing tools. But if your objective is related to increasing insect biodiversity, or providing habitat for bobwhite quail, or attracting a prairie chicken lek to your property, progress on all these fronts can easily be monitoring by lending an ear to the land in question.

Engaging more intentionally with the sounds of the world can lead to scientific insight, effective land management, compelling stories of nature, and surprisingly visual art. Most importantly though, at least for us prairie appreciators, soundscape ecology reminds us simply to quiet our voices and thoughts so that the prairie, too, might speak.