This post is written by Emma Greenlee, who recently completed her Hubbard Fellowship year here at The Nature Conservancy in Nebraska. Emma is now moving on to graduate school, where she’ll have the chance to study prairies in even more depth than she did with us. As her independent project during her Fellowship, Emma helped us evaluate the way our restored prairies contribute toward pollinator resources. Specifically, she counted the number of flowers and flowering plant species available in both remnant and restored (planted from seed) grasslands at our Platte River Prairies site. She is sharing some of the highlights from her findings in this post:

During my time as a Hubbard Fellow I conducted an ecology research project comparing flowering species community composition and floral resource abundance in remnant and restored prairies at the Platte River Prairies preserve (PRP). The Nature Conservancy has been doing restoration work along the Platte River since the 1990s. That work was initially done in conjunction Prairie Plains Resource Institute, a restoration-focused NGO based in Aurora, Nebraska. Prairie Plains has immense expertise in constructing restorations from a high-diversity of locally sourced native prairie seeds.

The Nature Conservancy’s goal for restoration work at PRP is to increase habitat connectivity among prairie sites. The philosophy with which TNC has approached prairie restoration in this area is not that restored prairies should be exact replicas of nearby remnant sites. They don’t need to have the same species composition as neighboring remnants, they need to contribute to the area’s prairie habitat connectivity. That, in turn, will benefit the native species persisting in today’s fragmented prairie landscape. In my project, I investigated what floral resources for pollinators (aka flowering plants/forbs) look like across these remnant and restored sites.

Although TNC’s restoration practitioners and land managers do not seek to create prairie restorations that are identical to their neighboring remnants, it is important to understand how both compare in terms of the resources they provide to prairie communities. That way, we can assess our restoration and management approaches and alter our techniques if needed. There are so many aspects of a prairie ecosystem that one could measure to determine this, but because I’m really excited about plant community ecology, I chose to approach my project from that direction. In addition, I wanted to address the role plants play in supporting the prairie ecosystem, and thinking about floral resources for pollinators appealed to me as a way to do this (while still focusing my data collection efforts on the plant community!).

Catsclaw sensitive briar (Mimosa quadrivalvis var. nuttallii), July 2022. Photo by Emma Greenlee

I selected five sites at PRP that contain a remnant and an adjacent restored prairie undergoing similar management. Every two weeks, from early May through mid-October, I collected data within a designated sampling polygon in each of the remnant and restored prairie sites I had selected. Collecting data through time in this way allowed me to see how the prairies changed throughout the season, and this was a highlight of my project.

From seeing the first flowers of the year, like fringed puccoon (Lithospermum incisum), to the new plants I learned about throughout the season like catsclaw sensitive briar (Mimosa nuttallii) and Illinois bundleflower (Desmanthus illinoensis), to the bobolinks I heard singing and the cool invertebrates I saw along the way, I noticed something new every time I went out to collect data. Especially satisfying was the day in June when, as if a switch had flipped, the native tallgrass big bluestem had suddenly overtaken the invasive smooth brome that had been widespread in many sites early in the season. Even though my project primarily involved collecting data on wildflowers, it provided me the opportunity to notice so much more.

.

Results and Discussion

In general, my results suggest that floral resources in remnant and restored sites at the Platte River Prairies were similar this year! The flowering species that were available in a given location, as well as their abundances, varied throughout the season, but I found no evidence that remnants or restorations as a group had more or fewer flowers than the other at any point during the growing season.

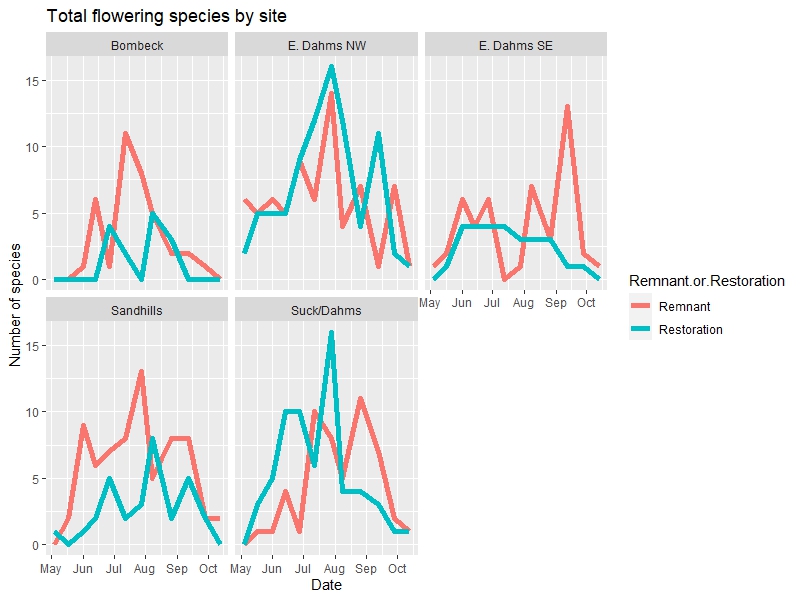

In fact, some of my results (see graph below) suggest that remnant and restored sites complement each other in terms of the flowering species they provide. This complementarity indicates that there are different floral resources in adjacent remnant and restored sites at a given time, but that remnants and restorations flip-flop throughout the season in terms of which offer more flowering species for pollinators. Because the paired sites I studied were located geographically near to each other, this suggests that insects are able to move between neighboring remnants and restorations to fulfill their needs throughout the season.

Within the above graph, the red and blue lines zigzag many times, with a remnant (or restoration) containing more flowering species, and then its paired restoration (or remnant) overtaking it to have more flowering species the next month, and then vice versa. This should overall be a positive for pollinators who are able to move back and forth between neighboring sites to fulfill their needs at a given time. (If you’re looking for a clear example of the pattern I’m describing, it’s especially visible in the East Dahms NW site (top middle graph) from August through October.)

Additionally, my results suggest that factors apart from a site’s status as a restoration or a remnant are likely responsible for much of the variation in flowering communities found at PRP. Some sites have sandy soils and hilly topography, while others are largely flat with a shallow water table (underground water is fairly near the surface) and wetland sloughs running through them. Variations like these shape the suite of plant species that is able to establish in an area. In the sites I studied it seems likely that factors like these (soils, topography, hydrology…) are important drivers of plant community composition in the patchwork of prairies along the Platte River, regardless of whether a site is a restoration or a remnant (see graph below).

On the above graph, circles represent remnants and triangles represent restorations, and each remnant/restoration pair is a different color. Most of the color-coded remnant/restoration duos are found close to each other on the graph, indicating floral community similarities. Interestingly, most of the restorations are also grouped fairly near to each other, as are the remnants! This suggests some community similarities among remnants overall and among restorations overall, but it would take more statistics than I accomplished on this project to find out what those might be!

We can’t draw too many firm conclusions from only one year’s data––factors like that year’s weather, the number of sites I collected data from, and each site’s management all may play a role in the patterns I saw. However, this is still useful information that can be built on in the future, or simply serve as a single-year snapshot of a few aspects of prairie community health on the preserve. In general, what I found this year suggests that restoration work at the Platte River Prairies preserve is largely effective in increasing prairie habitat connectivity by the metric of providing floral resources for pollinators. This is encouraging news, and suggests that the methods used here (and in many other places!) of restoring prairies with a diverse mixture of locally sourced native seeds are sound and contribute to the prairie patchwork landscape of central Nebraska.

I learned so much from this project and from the Fellowship more broadly, and I appreciate everyone who has read my blog posts along the way! It’s been a pretty cool privilege having such an enthusiastic audience to share some of what I’ve learned this year with. Next I’ll be pursuing a Master’s degree at Kansas State University studying plant-pollinator interactions in prairie, and I’m very excited for that! I also look forward to finding new ways to share my prairie enthusiasm with a wide audience.