This post is written by Kim Tri, one of our two Hubbard Fellows for this year. Kim is an excellent artist, as well as an ecologist, writer, and land steward. As you can see, her drawings of animals are exceptional.

If you take a look at the official taxonomy of the red fox (Vulpes vulpes), and you follow it up the classification ladder to the Order level, you’ll see that it belongs to the order Carnivora. The meat eaters. It keeps company there with such formidable predators as mountain lions, wolves, and polar bears (oh my!). But if you know much about foxes, you know that they’re real punks. They don’t care what we’ve labelled them.

A drawing inspired by the indiscriminate dietary habits of foxes. Everything inside of the fox itself are things that they will eat if they can get them. Marker drawing by Kim Tri.

While they do eat meat, as much of it as they can, they are not obligate carnivores—creatures that subsist only on meat. Felines are obligate carnivores. Foxes, however, eat a diet quite similar to that of the poster child of omnivory, the raccoon. Omnivores are real opportunists, eating whatever is available. During the summer and fall, nearly 100% of a fox’s diet may consist of insects and plant matter such as fruit and seeds. During these seasons, these represent the most abundant and least energy-intensive of food sources. I imagine that during the summer on our prairies, a fox could subsist entirely on grasshoppers if it desired; it could just sit with its mouth open and let them hop right on in. It is during the winter when foxes rely on what most people think of as more typical prey, such as small mammals and carrion. If you want to kill some time and your boss isn’t looking, I recommend looking up videos of foxes hunting mice in the snow. They’re quality entertainment.

To get a real good idea of what comprises any given animal’s diet, take a look at its dentition. Below, I’ve included some quick sketches comparing the teeth of different native mammals.

First, the fox. It does have the pronounced canines and big shearing carnassials of a carnivore, but in the back of its mouth also possesses flat molars for grinding plant matter. You can see evidence of our species’ omnivory inside your own mouth—our canines aren’t just there to look pretty, after all.

Compare this with a raccoon. Their array of teeth is quite similar, though a raccoon’s canines are more blunt and less finely developed, being more adapted to crunching crayfish than catching mice.

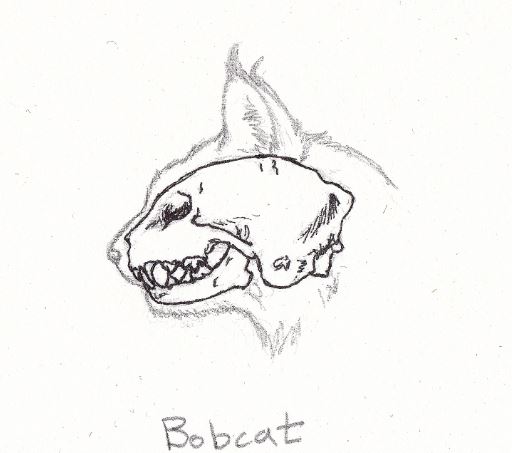

The bobcat, an obligate carnivore, as you can see only possesses the teeth developed for meat eating: canines, premolars, carnassials, incisors. If you have a pet cat who permits such familiarities, you can take a look at these teeth for yourself. Fun fact: according to the people who take it upon themselves to research such things, felines also cannot taste sweetness. Since they don’t eat fruit or other plant matter, it does not make sense for them to be able to detect the ripeness of fruit, which is what the ability to taste sweetness is really all about.

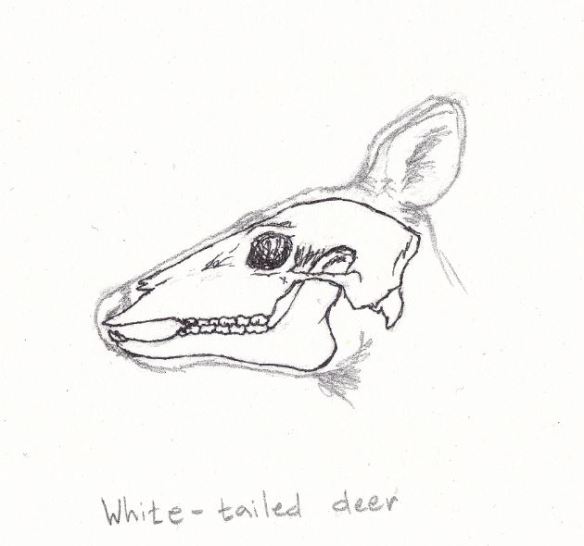

The white-tailed deer has only flat grinding teeth, as well as a single set of lower incisors, which it uses for stripping bark to eat during lean times. There are actually species of deer which possess formidable canines, but they are more omnivorous and definitely not native to this country.

And now back to foxes. It is partially the red fox’s ability to eat anything that has allowed it to thrive in the face of human expansion. Our overflowing trash cans, roadkill-covered roads, and unattended pet dishes are like a buffet. The fox’s big cousin, the coyote, has experienced similar success. A large part of this success is also due to human’s extermination of large predators such as wolves and cougars, as well as our introduction of the fox to new areas, but that is a different and more contentious subject.

On the flip side, there is another fox native to Nebraska, the swift fox (Vulpes velox), which has not done so well since settlement of the country. This has much more to do with habitat than diet. It is strongly tied to grassland habitat and used to range nearly statewide. Since much of its original habitat has been converted or degraded, it is now only found in the sparsely populated grasslands of the panhandle and is a state-listed endangered species. The red fox, being a habitat generalist, has taken advantage of the range vacated by its smaller cousin.

Unfortunately, I must admit that I’ve never actually seen a red fox on our prairies, though I feel safe in assuming that they are here. After all, this is wonderful habitat for them, with lots of wooded edges, prey, and forage. They are generally fairly elusive creatures—I’ve seen more wild wolves in my life than I have foxes. Though with the arrival of winter, I’m excited to keep an eye out for little canine tracks in the snow.