Many of the prairies we manage have pretty degraded plant communities, characterized by low plant diversity and dominance by a few grass species – including the invasive Kentucky bluegrass (Poa pratensis). Our primary objective for these prairies is to increase plant diversity, which, in turn, bolsters ecological resilience and improves habitat quality for a wide range of prairie species. Because bluegrass is so pervasive in our prairies, we’ve had to modify our objectives and strategies from those we use to address most other invasive species.

Kentucky bluegrass can stifle plant diversity by crowding out other plants. In many prairies degraded by years of overgrazing and/or broadcast herbicide use, bluegrass is now the dominant plant species and few other plants can compete with it.

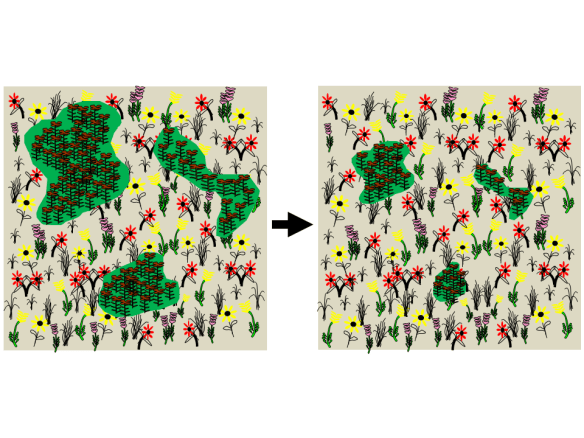

When attacking invasive plant species, a common strategy is to contain, and (hopefully) shrink, patches of invasive plants in order to protect plant diversity in non-invaded areas. In the case of Kentucky bluegrass, however, we have to take a different approach because the species already spans the entire prairie. Kentucky bluegrass acts like a thick blanket of interwoven stems, roots, and rhizomes – smothering most other plant species beneath it. Because our goal is to increase plant diversity, we want to make that blanket thin and porous enough that a wide variety of other plant species can grow up through it.

An illustration of a floristically diverse prairie (left) with several large patches of an invasive plant. When dealing with many invasive species, we can focus on reducing the size of infestations in order to restore a more diverse plant community.

Kentucky bluegrass acts as a thick blanket that smothers most other plant species. In a case like this, we need to manage the prairie in a way that increases the mesh size of that blanket and allows a more diverse plant community to poke through.

Our primary strategy for suppressing Kentucky bluegrass is the periodic application of prescribed fire and grazing. We can weaken bluegrass by burning prairies when bluegrass is just starting to flower and/or by grazing prairies harder in the spring than in the summer. We mix those treatments with rest periods within a patch-burn grazing regime. The result has been a steady increase in plant diversity in most of our degraded prairies.

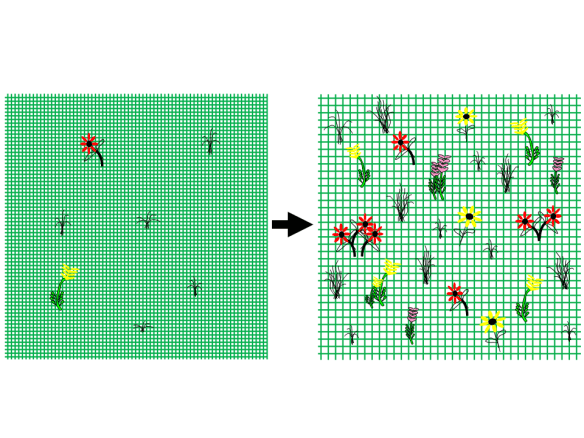

If we were fighting a different invasive species, we might expect that if plant diversity was increasing, the amount of territory occupied by the invasive species would be decreasing. With Kentucky bluegrass, however, our bluegrass blanket is getting thinner, but still covers the whole prairie – something that shows up clearly in data I’ve been collecting over the last decade. Through the use of nested sampling plots of 1m2, 1/10m2, and 1/100m2, I’ve been tracking plant diversity and floristic quality through time, along with changes in the frequency of various plant species (the percentage of plots in which they occur). Over the last 8-10 years, as plant diversity within 1m2 plots has increased, the frequency of Kentucky bluegrass has stayed about the same. Even at smaller plot sizes, which are more sensitive to changes in the frequency of very abundant species, bluegrass is still in nearly every plot.

We also have a number of restored (reconstructed) prairies in and around our remnant prairies. Within restored prairies, plant diversity is in pretty good shape, but Kentucky bluegrass is rapidly invading. In one particular prairie, Kentucky bluegrass is now in almost 90% of 1m2 plots and more than 50% of 1/100m2 plots. That sounds bad, but as bluegrass becomes more abundant, plant diversity – and the frequency of other prairie plant species – is actually holding steady. There are a few small areas in which bluegrass appears to be forming near monocultures, but for the most part, it looks like bluegrass is just filling in around the other plants instead of actually displacing them. My guess is that some soil conditions provide such ideal growing conditions for bluegrass, it’s going to be king of those areas no matter what we do. Elsewhere, however, I think our management is preventing it from becoming dominant.

Here’s the take home lesson for me: When trying to manage for plant diversity in the face of a pervasive species such as Kentucky bluegrass, it’s more important to track plant diversity than to worry about how much territory bluegrass occupies.

Just consider the data from our prairies… if I concentrated only on how much Kentucky bluegrass is in our prairies, it would look like we’re failing miserably in our management attempts. We’ve got just as much bluegrass as we ever did in our degraded remnant (unplowed) prairies, and we’re quickly losing ground in some of our restored prairies. However, my data also shows that plant diversity is increasing in remnant prairies and holding steady in restored prairies. Since the ultimate goal is to have a diverse plant community, that’s success!

Click here to see a PDF showing some of the data I mentioned in this post.