I presented this argument to a Nebraska symposium on grassland birds in 2008 and managed to escape relatively unscathed. Now I’m testing my luck with a wider audience. At least no one can throw things at me through the computer…

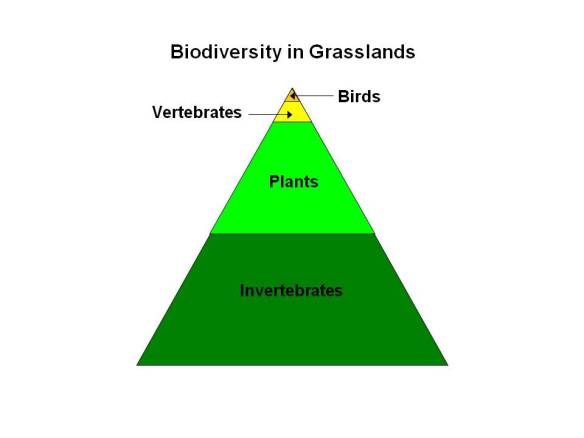

Let me start by saying that I’m a big fan of birds. I really enjoyed working on my graduate research, which focused on grassland birds and their vulnerability to prairie fragmentation. I also think birds are generally pretty and interesting. However, the truth is that prairie birds make up only a tiny percentage of the species in prairies (most of which are invertebrates, followed by plants).

Grassland birds make up a tiny percentage of the species living in a prairie - the vast majority of which are invertebrates and plants.

However, grassland birds are often held up as indicators of whether or not a prairie – or a prairie landscape – is “healthy” or “high quality.” A common refrain in prairie conservation goes something like this; “If we have our full complement of grassland birds in this prairie and/or landscape, it’s a good bet that all the other species are also doing well.” Unfortunately, while prairie birds are relatively easy to study and monitor, they may not do a good job of reflecting how the rest of the prairie is doing. Let’s look at some of the most important attributes of prairies and some of their major threats – and consider how well birds correlate with them.

Species Needs – Survival, Reproduction, and Dispersal.

First and foremost, species have to survive and reproduce in order to persist in a prairie. This applies to every species, from large vertebrates to tiny invertebrates and the entire suite of plants. It’s important for us to know that grassland birds are surviving and reproducing, but can they tell us whether other species are doing the same? You could argue that because they eat insects, grassland birds could have an impact on the survival of some insect species. That’s true to a point, but grassland birds are generalist feeders – they tend to eat whatever insects are easiest to catch at any particular time – so while the abundance of grassland birds might impact the overall abundance of insects, you can’t really tie the presence of a particular grassland bird species to the survival of a particular insect species (or vice versa). In other words, the plight of a rare leaf hopper or butterfly species is unlikely to be correlated with grassland birds. Nor are grassland birds good predictors of plant species survival – the presence of meadowlarks or Henslow’s sparrows tell us nothing about whether or not compass plant or leadplant is thriving. Grassland birds require certain habitat structure types (short vegetation, tall/dense vegetation, etc.) but they don’t much care whether that vegetation consists of smooth brome and sweet clover or a large diversity of native plants.

Henslow's sparrows are a bird of conservation concern and their presence in a prairie can be seen as a conservation success. However, although they tend to require fairly large prairies, and can indicate the presence of certain vegetation structure types, they don't indicate whether or not a prairie has a diverse plant or insect community.

In addition to basic survival, animal and plant species need to be able to move around the landscape in order to recolonize places where they have disappeared, and to maintain genetic interaction between populations (important for genetic diversity). In landscapes where prairies exist as isolated remnants, moving between prairies becomes very difficult. Corridors of prairie vegetation between prairies become important in those landscapes, and prairies near each other provide better opportunities for interaction within species than do more isolated prairies. Because most grassland birds fly south at the end of each season and return the next year, (and the ones that don’t can still fly long distances between prairies) they don’t rely on those physical connections between prairies like most other animals and plants do. Since grassland birds are pretty unique in terms of long-distance flying ability, they are a poor indicator of conditions that affect less mobile species.

Ecological Services and Ecological Function – Pollination, Seed Dispersal, etc.

Apart from the needs of individual species, prairies rely on certain processes to keep everything humming along. Pollination and seed dispersal are two good examples. Both affect the viability of prairie plant species, and neither has much to do with grassland birds. Pollination primarily relies on plant diversity and bees – the most important pollinator group in prairies – and both plant diversity and bees are pretty disconnected from grassland birds. We don’t know much about the role of prairie birds as seed dispersers, but it’s a good bet that they do very little seed dispersal during the summer when they’re primarily eating insects. The role of migrating grassland birds as seed dispersers would be an interesting thing to study – but our use of grassland birds as indicators of prairie quality is always based on their presence during the breeding season. If you were going to measure whether or not pollination and seed dispersal were functioning adequately, you’d likely evaluate the diversity of plants, the abundance of bees, and some of the potential obstacles to seed dispersal (tree lines, isolation of prairies, etc.), but I don’t think measuring grassland birds would tell you much.

Resilience – Redundancy and the Ability to Withstand Stresses and Invasive Species.

One way to think about the resilience of a prairie is as a measure of how well the prairie can bounce back from stresses. For example, species diversity adds resilience to a prairie because when many species are present – especially when they overlap in the roles they play – the loss of an individual species can be a relatively minor blow. If there are dozens of bee species pollinating flowers in a prairie, a disease that wipes out one or two species will probably not have a huge impact on seed production. A diversity of plant species can also help to dampen the impacts of an event such as a severe drought or intensive grazing that temporarily weakens the vigor and growth of dominant plant species. When there are lots of plant species present, the weakening of some leads to increased growth and abundance of others. This helps maintain a stable supply of food for herbivores, and also helps prevent encroachment by invasive species that might otherwise take advantage of the weakened plant community.

Grassland birds may help bolster the resilience of a prairie in some ways. They might, for example, help suppress an outbreak of grasshoppers by focusing their feeding on that easy-to-find prey species, and thus limit its abundance. However, as discussed earlier, they don’t have much to do with pollination, nor would they help provide food for herbivores during a drought.

Threats to Prairies – Habitat Fragmentation, Invasive Species, Broadcast Herbicide Use, and Chronic Overgrazing.

One of the best arguments for grassland birds as an indicator of prairie health is that they are vulnerable to the loss and fragmentation of grassland habitat. This is true. A diverse and successfully reproducing community of grassland birds requires relatively large and unfragmented grassland. In addition, because some grassland breeding birds need short vegetation and others need tall/dense vegetation, a diversity of birds can indicate a diversity of available habitat structure – and that’s important to many other wildlife species as well. Greater Prairie Chickens are often promoted as particularly good indicators because they are a single species that needs both large grasslands and a diversity of habitat structure.

However, there are a couple of other things to consider. First, while some grassland bird species need large prairies, we don’t really know whether the minimum area required by grassland bird species is larger or smaller than that required by plant or insect species. We know that many prairie plant species have survived for a very long time in tiny isolated prairies. But because individual plants of many species can live almost indefinitely, due to their ability to generate new plants through rhizomes and other asexual means, the populations of plants in those tiny prairies could be in a death spiral due to the lack of genetic interaction with other populations. You could make the argument that plants need much larger prairies than birds (thousands of acres, perhaps?) in order to maintain genetic fitness. We simply don’t know. And we know even less about the prairie size needs of insects.

Second, while grassland birds do require fairly large grasslands, most don’t actually require PRAIRIES. Prairie chickens and many other grassland bird species have benefitted greatly from Conservation Reserve Program (CRP) fields that have added large numbers of acres of switchgrass, brome, and low-diversity grasslands to agricultural landscapes. However, those same CRP fields have done very little for native wildflower populations or pollinator insects (or other insects that rely on diverse communities of native plants) so the increase in grassland birds in landscapes with CRP doesn’t really tell us much about the health of most other prairie species.

This smooth brome-dominated grassland is of very little to most prairie species, but would provide relatively good habitat for some grassland bird species (except for the trees in the background).

Because grassland birds can live comfortably in grasslands made up of a few native grasses, or even non-native grasses, they are poor indicators of the impacts of most invasive species – a major threat to prairies. Similarly, broadcast herbicide use that greatly reduces the number of plant species in a prairie has little impact on the grassland birds nesting there. Finally, a prairie that is being overgrazed would certainly have different bird species than one that is not being grazed at all, but a prairie that was chronically overgrazed for decades – and then managed well again – would have a pretty low number of prairie wildflower species but a very nice-looking grassland bird community.

One threat that grassland birds can be an excellent indicator for is tree encroachment on prairies. Most grassland birds avoid nesting anywhere near even a solitary tree, let alone a grove of them, so a prairie with few birds could indicate a tree problem. On the other hand, it’s pretty hard to miss a bunch of trees growing in a prairie…

Summary

Here’s the real point. Grassland birds are an important component of prairies. A prairie without all of its appropriate prairie bird species, or in which those species are not successfully raising broods, is missing something valuable. Improving grassland bird success in prairie landscapes is an important and worthwhile objective. At the same time, however, a prairie that has a full complement of successful grassland bird species doesn’t necessarily have diverse plant and insect communities, functioning ecological processes, or a low risk of invasive species or other threats. In other words, grassland birds are an important component of high quality prairies, but their presence and/or success doesn’t necessarily mean a prairie is high quality.

Now that I’ve spent 1,500 words bashing prairie birds (I really do like birds…) the relevant question is, “What SHOULD we use as indicators of prairie conservation success?” I wish I had a simple answer. Part of the answer, of course, depends on how you visualize prairie quality (see my earlier post on this subject) because evaluation needs to reflect objectives. But if our vision of a high-quality prairie includes species diversity, habitat heterogeneity, and other complexities, our evaluation methods will have to be complex as well. Figuring out how to “take the pulse” of prairies may be the most important conservation challenge we face, because without that information we can’t design effective conservation strategies.

While we still have a lot to learn about how to take that pulse, it’s clear that we’ll have to do more than just count birds…

Chris,

What I hear you saying is birds are less discriminating in their local habitat (because they are so mobile?) so we should treat them as visitors rather than citizens when trying to evaluate the health of a prairie. From an urban perspective, tourists are important to an economy as supplemental revenue but it’s the inhabitants of a city that provide it’s vigor and ongoing robustness. There’s definitely an interaction between tourists and inhabitants, but measuring the health of a city means paying more attention to the microeconomic issues of its citizens.

Do you see ecology in an economic sense; i.e., efficient allocation of resources directed to ongoing survival and genetic distribution? It’s a discipline with tools to measure the impact of small changes in resource availability on overall system performance. Of course, that reduces a prairie to a series of math functions and system constants – hardly a way to view such a dynamic place!

Mel – the “visitors” aspect of birds using prairies is most important in terms of the relevance of birds as predictors of inter-prairie travel. In other words, birds can move between prairie much more easily than other species, so they’re poor indicators of whether or not other species can move around the landscape. And, because they don’t disperse from prairie to prairie like most other species (they disperse from local prairie to Argentina, for example, and then back) they’re just a whole ‘nother animal, so to speak… The third point is that while birds are discriminating in their habitat choices, the criteria they use are not the same as many other species, making birds poor predictors of the presence/success of other species.

Your economics analogy is really interesting. Not one that I’ve thought about, but one that I’d like to. I’m not sure I’m enough of an economist to understand that field well enough to draw comparisons… Thanks for making me think!

Great post, Chris, really thought provoking. And seems likely we really need to think more “outside the box” about prairies. We’ve come a long way from the old days of thinking of them as deserts because they lacked trees, but it seems to me we are perhaps in a bit of a rut in how we view our prairies, and there is oh, so much we don’t know or understand about them.

Further, methinks this may have some bearing on the current discussion in Missouri, of patch burn grazing to encourage prairie chickens and other birds.

I think it DOES probably have some bearing on the current discussion in Missouri, but I want to be clear that it was not written as a statement on that. To me, that discussion is being framed by some as plant people against bird people, and I think that’s both erroneous and unhelpful. I know many of the MDC biologists well enough to know that they are not “bird people”, but are prairie biologists (and good ones) trying to improve prairies. Some may disagree with their methods, but I’m hopeful that people will come together, agree that prairies are not exclusively about either flowers or birds, and find ways to experiment with management strategies that may be helpful in maintaining biological diversity. Throwing rocks at each other probably isn’t going to help anything. Missouri is the envy of many other states (including mine) in that the state is crawling with prairie biologists and enthusiasts. Often, that’s a good thing. In this case, we’re seeing one of the disadvantages. Lots of people who care deeply about an important natural resource, but who disagree with how it should be managed.

Near Denison Iowa I observed several bobolinks male in the spring staking out territories. The field near a small river was brome and other unidentified grasses. According to the land owner the field has been a pasture since the land was purchased in 1856. I am sure the pasture has never been plowed but over grazing and so call pasture improvement has killed the prairie. The bobolinks have been return every year as long as there was a physical structure to support their nest and enough food. There apparently is both of these even if the physical structure was not native prairie plants.

A beautiful supporting example. Thanks Glenn.

My experience with bobolinks here on the Platte River is that we see them in our prairies much more abundantly after the first cutting in nearby alfalfa fields. They seem to prefer alfalfa fields (Dickcissels do too) to prairies until the hay equipment comes through, and then they decide prairies might not be so bad…

Aah, you say it so well, Chris, grassland birds are not good indicators of prairie diversity. All that they need is adequate structural diversity for nesting and mobility; adequate forb diversity for abundant insect, seed, and green browse foods; and lots of open grasslands for courtship and breeding. Diverse prairie can and should be a part of this habitat because it can provide more stable habitat than simpler species complexes but even if optimumly managed, diverse prairie may not provide habitat for optimum grassland bird densities. Average prairie-chicken density in high qualilty, grazed native prairie is only one bird per 53 acres whereas Westemeier and Simpson achieved one per 10 acres in small blocks of brome, timothy, redtop, alfalfa, and alsike clover in Illinois.

Trager also hits on a good point in the Missouri pbg debate. High qualty prairies were bought to preserve rare prairie plants but also as intregral part of the prairie-chicken recovery plan from 1984-2004. However, prairie chickens and other grassland birds abandoned these prairies when they were idled two years out of three and only hayed or burned. Without having acquired other grasslands or cropland that could be planted to other grass and forbs, managers decided to explore more diverse prairie management to which grassland birds responded. Now the debate ensues, is patch-burn grazing, which appears to be good for birds, good or detrimental to certain prairie plants? Heretofor, the only thing that had been greater than the prejudice against grazing prairies, was the prejudice against using non-prairie for habitat for prairie-chicken and other grassland birds. Hopefully, discussions will result in the resolution and alleviation of both prejudices so we can get on about plant and animal conservation.

Thanks for the context Steve. I like prairie chickens. But I like them even better in prairies! I can see how people could have a hard time accepting creating tame grass habitat for them, even if it helps conserve the species. As you say, prejudices aren’t all that helpful…

An open mind, however, is.

Chris,

I just came across your blog, can’t wait to return to read more.

Heather

The monitoring approach NPS takes is to develop a set of vital signs. Park managers together with monitoring staff choose a suite of elements and metrics that they feel are important to track. It varies by park, but typically includes plant species communities (metrics include diversity, richness, guild ratios), breeding birds (richness presence and spatial distribution), aquatic invertibrates and fish, and deer. We can get status and trends through measuring vital signs. The tricky part is figuring how to integrate the results together with management history, for a more cause and effect understanding.

Thanks Sherry – I think you’re right, the hard part is making the causal connection. It’s one thing to see changes, but understanding why they’re happening, and more importantly, how to influence them, is the key. And it’s really hard.

Pingback: Why Are We Spending So Much Time Studying Birds? | The Prairie Ecologist

Pingback: Changing Our Focus | The Prairie Ecologist

i love it

Pingback: How big do prairies need to be? | The Prairie Ecologist

Pingback: Let’s talk about (shudder) monitoring | The Prairie Ecologist

Hi! I’m a student currently working on a prairie management plan in Milwaukee. I was wondering about the pyramid diagram showing the biodiversity of species in prairies. For my project we are identifying a suite of prairie indicator species and I’d like the number of indicator species we chose to represent the biodiversity proportions of a typical healthy prairie. So for example we want to choose mostly invertebrate species, followed by plants, followed by vertebrates, and we are still contemplating whether to include bird species (due to the public interest in them). Do you have any resources you could share about how you came up with these proportions or came up with the diagram? Thank you!

Hi Haley, don’t read too much into the proportions of the illustration. It was simply meant to depict that vertebrates make up a much smaller proportion of species than other groups.