Why is sweet clover the target of aggressive control by some prairie managers and largely ignored by others? After talking to a number of people across the Midwest and Great Plains, I think there are a couple of things happening. First, the usually biennial sweet clover can be very abundant and showy in the years it blooms, but is harder to find in other years. I think some prairie managers see those big flushes and mistake abundance for aggressiveness. However, I also think that some soil/precipitation/latitude(?) conditions may lead to real negative impacts from sweet clover on plant diversity.

One of the lessons that’s been strongly reinforced for me this summer is that it can be difficult to extrapolate successful prairie management/restoration strategies from one region to another. Just during the last several months, I’ve visited prairie managers in Nebraska, Indiana, Missouri, and South Dakota and I’ve seen tremendous variation between (and even within) those states in terms of which species are invasive and which are not. It’s dangerous to assume that just because a species like sweet clover isn’t causing problems in one prairie, it won’t cause problems in another. I hope we’ll eventually learn enough to accurately predict when to worry and when not to, but in the meantime, it behooves prairie managers to carefully evaluate species at their own sites.

Yellow sweet clover. This exotic species is still planted in some wildlife and ground cover grassland plantings because of its purported wildlife value and cheap seed. However, it appears to be invasive in some places and/or situations.

I’ve been working with prairies along Nebraska’s Platte River for nearly 20 years now, and my observations have led me to conclude that sweet clover is more of a big ugly plant than a true invasive species in those prairies. Years of data collection on my plant communities support those observations. That annual monitoring work entails listing the plant species I find in each of about 100 1m2 plots across a prairie. Those plots are stratified across the prairie so the site is evenly sampled. Once I have those plotwise species lists, I calculate the floristic quality (FQI) inside each plot, a calculation that takes into account both the number of species present and the average “conservatism” value of those species. I can then look at changes in mean floristic quality over time to help me see how the plant community changes over time. I monitor a few prairies annually, and others on a periodic basis.

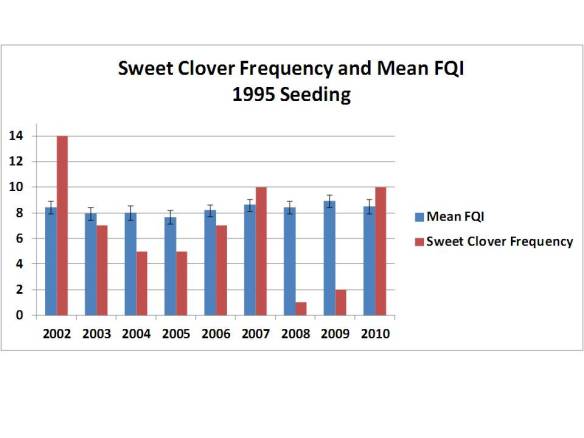

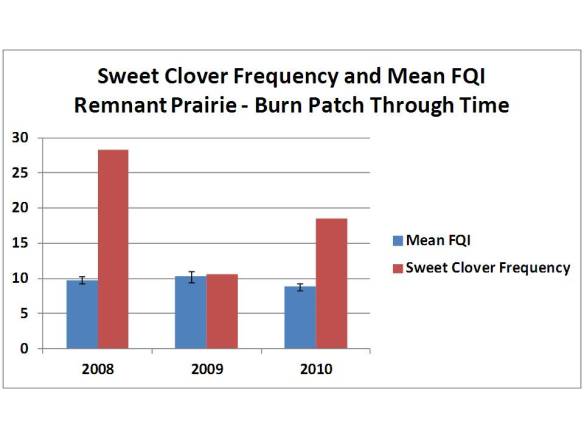

Those data show the same thing I’ve seen observationally – sweet clover changes in abundance from year to year (though not as much as it appears visually), but the species doesn’t increase in abundance over the long term and doesn’t appear to negatively impact floristic quality. Below are graphs from three sites that show both sweet clover frequency (% of plots occupied by sweet clover) and mean floristic quality. Two of those sites were annually grazed during the data collection period, and the other was only grazed once – toward the end of the sampling period. Cattle grazing almost certainly helps control sweet clover because it is one of their favorite plants to eat, but I don’t think sweet clover is causing me problems where I don’t graze either.

What my data don’t show is the flush of tall blooming plants that happens every other year or so. I’m just counting whether at least once sweet clover plant is present in each of my small plots – not how big it is, or whether or not it’s blooming. Nevertheless, sweet clover frequency changes from year to year but doesn’t appear to correlate at all with changes in mean floristic quality.

Nine of years of annual data from a 1995 prairie restoration seeding. The site has been under patch-burn grazing during each of the nine years of data collection. Sweet clover is never abundant at this site, but has also not increased over time, even through years of drought and heavy grazing. Error bars for floristic quality indicate 95% confidence intervals.

.

Sweet clover was present in between 22% and 42% of 1m plots in this restored crop field, planted in 2002. Though the sweet clover frequency varied from year to year, the mean floristic quality of the plant community increased between 2004 and 2008 before leveling off after that - apparently independent of sweet clover. Sweet clover data from 2008 was eliminated from this graph because I later questioned whether I'd confused black medick and sweet clover in some plots. This site was not grazed except in 2009.

.

These data are from a remnant mesic prairie under patch-burn grazing. Instead of being stratified across the entire prairie, these data are from a single patch that was burned in 2008, and that same patch was sampled again in 2009 and 2010. It was grazed very hard in 2008. In 2009, no new patch was burned, so it was grazed hard again, but then fenced out in early June. In 2010, the site was not fenced out, but received only light grazing while cattle focused on another portion of the site that was burned. These data are from only about 30 plots per year.

I feel pretty good about ignoring sweet clover and focusing on more invasive species on our prairies. Both my observations and data support that strategy. However, as I said earlier, just because the species doesn’t appear to be problematic for me doesn’t mean it isn’t an invasive species in other prairies. It’d be great if we could compare data similar to what I’m presenting here from a number of sites to see if sweet clover is acting differently in different places. Without data, it’s hard to know whether or not people are just interpreting the “invasiveness” of sweet clover in different ways. For now, my answer to the question, “Is sweet clover really invasive?” is still the same…

Maybe.

David – as promised. I hope it’s useful.

Chris,

You’re a good guy. Thanks for accommodating me. I think it is great you have data. I wish I had the same for all the sites I work on. Good job!

Your data is interesting and intriguing. I am struggling a bit with it as I am not familiar with grazing impacts or the flora of Nebraska. Maybe you can help me out and give me a feeling “broadly speaking” as to what the average FQI would be for a high quality, moderately degraded and a severely degraded site? I also am curious what your average CC is?

I am assuming that you are counting both first and second year plants. What jumps out at me is how low your sweet clover numbers are. I routinely see first year sweet clover infestations where one can reach down and grab ten plants or so in one hand full. These same areas have far fewer plants (but very conspicuous) in the second year but you can imagine how intense the competition must be. Maybe if I went through the exercise of counting sweet clover in quadrats distributed throughout the prairie the number would be much lower? Likely, but what does it really mean? Often, a site’s most conservative plant species are concentrated in small areas. If these are the areas worst affected by sweet clover, is there a risk that species richness will be negatively impacted? Curious as to how uniformly represented sweet clover is among your sample quadrats?

Does it make a difference as to what “good” and/or what “bad” plants are competing with sweet clover? I believe I have mentioned before that I often see a favorable relationship between sweet clover and cool-season exotic grass like smooth brome or quack grass. I assume that it is the nitrogen fixation of the sweet clover that is helping the exotic grasses along but I don’t really know for sure. What I do know is that repeated fire along with sweet clover removal greatly weakens the dense non-native grass sod on most dry to dry-mesic sites. I am curious as to whether your species counts are similar among quadrats and among the three sites you surveyed?

I walked through a 90 acre planted prairie the other day with the owner. The tall grasses were waving beautifully in the breeze. He was extremely frustrated with sweet clover management and told me he is going to convert it all to soybeans if he can’t find a way to manage it effectively. As his words reached my ears, my eyes were riveted on the ground observing first year sweet clover plants: acres upon acres of them. I’m guessing that at least 50 acres are severely infested. The guy owns prairie and savanna remnant too. We also just started to help him with a trout stream restoration. He is doing the right things. I want to encourage him. I say “I think we can help you.” Fortunately, this is one site due to its lack of herps and early plant risers; we can use fire to help manage the sweet clover. But will the schedule hold, will the May weather cooperate? I hope so.

I am rambling on now. This is a sign that you got me thinking!

Thanks,

David

David,

Lots of things to respond to there… Ok, first, mean FQI at the meter square scale in my prairies ranges from 4 or 5 in degraded remnants to maybe 12 or so in nicer remnants. Most of our high-diversity restored prairies are in the range of 8-10 at this point. I’m hoping that our most recent seedings will get up into the 11-12 range, but I don’t know. On all of those sites, a “good” mean CC value is about 3. Species per meter square range from 5-6 on more degraded sites to 10-15 on nicer plant communities (restored and remnant alike). In southeast Nebraska, we have some hayed tallgrass prairies with big showy plant communities, and they can have mean FQI values of 25 or higher, and have about 25 species per square meter as well. Mean CC values in those prairies is maybe 3.7.

Remember that in my data, I’m just counting presence or absence of sweet clover (and other species) in each meter plot. In some plots, sweet clover can be fairly abundant – though that’s rare – but it’s either present or absent in the data. I don’t know how to answer your question about whether sweet clover could affect those higher-quality plant community areas. In my sites, sweet clover seems to be relatively evenly distributed across sites, though in some restored prairies, density is higher in places where we piled topsoil from wetland restorations (high N?) and sometimes in areas where we did prior tree clearing or other disturbances.

I’m not sure whether or not certain plant species are better or worse competitors with sweet clover. That could lead to some fun experimentation similar to what the FWS in the Dakotas is doing with Canada thistle.

On planted prairies, I wonder whether more plant diversity would reduce sweet clover, or vice versa? Or maybe both can happen, depending upon circumstances. Would two years of mowing when sweet clover flowers reduce sweet clover abundance (it seems to work for some people). If so, are there other species ready to jump in and take its place in that landowner’s property? If not, it might just be a temporary fix…

I don’t know – it’s a puzzle we’re not likely to solve any time soon…

Chris,

Thanks. That gives me perspective. Of course, it is still likely apple to oranges as far as applying it to Wisconsin.

My biggest take away from your blog so far is how different our (all blog contributors) experiences are with individual species and even the efficacy of similar management practices. It also appears that these differences cannot all be explained away by geography alone.

I wonder if there are yet to be defined global or regional “system” laws of ecological restoration that will help us identify system feedbacks but the needed correction (management practices) are specific and unique to limited geographical areas and/or geographical plant/animal communities?

Probably will never know in my lifetime!

David

If you are attempting to increase pollinators in your prairie, sweet clover is one “attractor”. Of course, there are plenty of other species as well. How much attention is given to insect, or more specifically pollinator species when maintaining or restoring prairie habitats?

Dan, no question it’s attractive to bees – particularly honey bees. I still don’t like it.

We do think about pollinator species when designing our prairie restorations, but figure that maximizing plant diversity will be the best way to achieve and sustain that objective. NRCS is now giving bonus points for habitat plantings that incorporate pollinators in their objectives, and have some guidelines for how to best do that. They have a minimum of 9 flower plant species (3 early, 3 middle, and 3 late season bloomers) in order to qualify,but encourage people to use more. It’s a great start – and at least gets people to consider the needs of pollinators.

Chris – thanks for the discussion of this issue and for posting your data. I agree – but only from my observations – that sweet clover here in my Wisconsin prairies doesn’t seem to affect the floristic diversity of the prairies. Some years, and in some places, sweet clover is particularly abundant and I remove as much as I can, but although it changes the look of the prairie – how many natives I can see easily – it doesn’t seem to have any affect on the actual diversity.

What do you think about Queen Anne’s Lace? I’ve had a similar experience with it – it looks terrible in years when it’s abundant, and hides the view of the natives – but I don’t think it impacts diversity. (I certainly hope this is true – I don’t think it would be possible to get rid of it – the seeds are everywhere.)

Your other observation – that different “weeds” cause problems on some prairies but not on others – is particularly interesting to me. One plant I’ve been thinking about for a long time is Eastern Red Cedar. It’s common on dry bluff remnants around here, but not at all abundant, and it doesn’t seem to be invasive. But in the Mississippi River valley – only about 12 miles west of here – it’s a huge problem on bluff prairies. It completely takes over the remnants unless it’s controlled. I’ve always wondered why that should be – what is so different about bluff prairies that seem so similar, but are just a few miles farther away from the river.

Marcie – great question on Queen Anne’s Lace. I don’t deal with it much here – just a few plants here and there at this point. From colleagues to the east, the consensus seems to be that it’s not a big issue. Ugly, but not dangerous… On the other hand, it could be that – like you – they realized they have to live with and are just rationalizing!

The cedar story you present is interesting. Around here it can be very aggressive in the absence of fire, but it’s a good and native component of our ecosystems. Is there a difference in the fire regime between the two sites you mention? Great question…

At least in many cases there’s no difference in fire regimes in most of the bluff prairies I see. They’re prairies that no one is tending – so there’s no fire, no cutting of brush. But there are bluff prairies on nearly every south-facing point around here, so I see a lot of them. The ones close to the river are often completely covered with cedar, but ones farther “inland” are much more open. If anyone ever studies this, I’d be very interested to learn what they find.

My experience with red cedar in southwest Minnesota seems to indicate that the degree of cedar infestation on remnants usually correlates with the length of time since they were actively grazed. Even currently grazed prairies have some cedar, but once the cows are off (our cattle base is declining here) the cedar expands very quickly. Prescribed burning is almost never carried out on these prairies, so it lets the cedar get off and running. At this point we are stuck mechanically removing large cedar thickets (tree often 20 feet tall and larger) that are taking over because the trees are too big to be killed by the light fuel loads still present. Once they are removed and fire is reinstated the recovery is dramatic.

It will be interesting to see if this happens on our bluff prairies. They were last grazed in the 1970s, and we’ve owned them since 2000. We’ve burned two of the four large bluff remnants we own – and we’ve only burned them once. So far we haven’t seen any increase in the cedars, and even in the two remnants that haven’t been burned, there are very few cedars.

Do you observe more birds which eat and spread Eastern Red Cedar fruits near the river?

Our land is about 12 miles from the Mississippi, so I can’t compare with land closer to the river. But I don’t think there would be that many more, or different, birds 12 miles away. Our land is very wild – we have 420 acres that we’re restoring, and the land around us is all woodland owned by absentee hunters, and old farms.

These data do seem to say that sweet clover abundance doesn’t affect FQI over this timeframe. I wonder what the FQI could be if there was no sweet clover at all ever. Is there a way we can measure that?

Stephanie – I’m not sure how we could answer that question… It’d be nice to know! I could reanalyze the data and pull out the sweet clover to make it look like it’s not there, but that obviously wouldn’t give us what we want to know, because nothing would be growing in that space. My guess is that sweet clover in my sites is just another species, and that removing it wouldn’t change the FQI or the plant community in any significant way. But it’s just a guess.

Chris – Good post. Are there any data available that include comparison to a control group, with the sweet clover supressed with mowing, pulling, etc. I applogize if I’ve overlooked it in the above data. Part of the reason I ask specifically about mowing is that I’ve noticed that in some areas where I mowed sweet clover in bloom last year has now become thick with 1st year plants this year. It’s a strange sight. In areas where I mowed a single strip last year there is a single strip of 1st year sweet clover this year. Although, the infestation in these strips is not monolithic, the outline is pretty clear. Could I be unwittingly making the problem worse by mowing? Maybe creating conditions condusive to sweet clover germination? As you suggested, and I agree, the issue is far more complicated than it would seem at face value. A good control group would ceratinly help to make conclusions more clear.

Bob – sorry for the delay in responding. I didn’t have a control in my data. I wasn’t collecting it with sweet clover in mind, so just went back and mined data to see if I could put something together. I think an interesting control on my sites would be fire alone – no grazing – to help tease out how much cattle are influencing sweet clover vigor/abundance.

Mowing seems to get mixed reviews – (as do other strategies…just read the comments on this one post!). It might be that mowing higher to allow surrounding plants to maintain more competitive vigor would help. Or, it might be that high mowing would just allow the sweet clover to rebloom! Might be worth a try, though, given the results you saw. And of course when you do it, you’ll want to leave some areas unmowed – or maybe mow some high and some low!

Chris, thanks for presenting the data you have worked so hard to collect.

The FQI values at your sites seem low to me. This indicates the areas you are working at must be degraded or are restorations. It has been my observation that Sweet Clover is more of a problem in restorations than undisturbed high quality sites. I wonder how your sites would compare to those with higher FQI values.

I have seen a number of weeds invade high quality sites. Teasel is one big offender. Yet even among the Teasel high quality plants persist. Certain other plants tend to form monocultures. Examples of these are Phragmites and Crown Vetch. The monoculture forming plants are the ones that would have the highest impact on a given plot, although averaged across an entire prairie there significance might not be as pronounced. Another consideration is the stage of invasion. The Sweet Clover population seems stable from your data. It might be prudent to control a few plants before they take hold, but once the population has stablized efforts would be better directed at other more recent invaders.

I have seen White Sweet Clover form near monocultures. It can be so aggressive that it forms a forest like canopy that precludes other species simply by starving them of light. Sweet Clover density seems to be highest in rich moist areas. The fact that your prairies receive less precipitation than the ones I’m observing in Illinois might be causing our different observations.

Regarding mowing, I am told that mowing high to remove only the flowering part of the Sweet Clover while impacting other vegetation as little as possible is best. Unfortunately in our area the managers only have one mower setting, lawn. Therefore, I have not been able to observe the differences personally.

James

Be careful about comparing FQI values from prairie to prairie… Mixed-grass and tallgrass prairie – and even prairies on varying soil conditions can be equally good “quality” but have vastly different potential FQI values. Also, remember that I’m looking at an average FQI value at the 1m scale, so it’ll be very different than an FQI value calculated at a prairie scale. The important numbers aren’t the actual values, but rather change over time.

The sites I included in the graphs are two restored prairies and one moderately-degraded remnant. My response to David gives you a feel for the range of values we see in my area and further east in the state. It’s not realistic to expect Illinois and Nebraska prairies to be similar in those values – regardless of degraded or non-degraded status.

Chris, Thank you for the explanation. I understand better now. FQI is heavily weighted for diversity. A larger area or an ecosystem containing a couple more species in a given plot would have a much higher FQI. Number of species does not necessarily determine importance for conservation. An unusual habitat with only one or a few very rare species would logically be a higher conservation priority than a diverse undisturbed but otherwise common habitat. In the Chicago Region the experts tell me an area needs to have a FQI of 35 or higher to be worth preserving. You are right that this number would not be comparable to a small plot or a completely different ecosystem.

James

A tool I use often for removing Sweet clover is a very sharp hoe. I like to cut off individual plants right at ground level during peak flowering, if cut too high the plant will branch out from the base and flower again. For larger colonies I use a gas trimmer with a 4 tooth steel blade, I cover 150 acres per year with these methods. In MN, Sweet clover left to go to seed will in time form a dense canopy as James has observed, then you have a mess and will likely have to mow the entire area in following years.

Individual plants can be pulled, roots and all if the soil is soft and moist, with leather gloves I also pull Canada thistle and get the root in good soil conditions. I have found by keeping Sweet clover from going to seed each year the population is managed with spot weeding methods only.

One example of a species being invasive in one area but not another would be cheatgrass. It is perhaps the most damaging invasive plant in the west, drastically changing plant communities, and yet a weak competitor in the east. I wonder if as a general rule, annuals and biannual invaders are less likely to replace plant communities in more moist environs with greater competition for space and nutrients, with perennial invaders being less likely to replace plant communities in drier environs with great competition for moisture? There are obviously exceptions and other variables, such as tolerance to fire-grazing, but I wonder if that works as a general rule? If so, queen ann’s lace might function merely as an annoyance in a vigorous tallgrass plant community, similarly to depfort pink and musk thistle.

Jarren – good comments. I’m not sure we can say that invaders are more damaging in drier west as a rule. I think it depends on the species and the “sweet spot” habitat conditions it requires. Buckthorn, for example, may turn out to be much less competitive in the west than the east (based on very early observations in Nebraska). It doesn’t seem to be spreading quickly in the west like we expect in the east – though it could just be a matter of time. Regardless, I would expect invaders to be like native species, and have habitat conditions in which they are most competitive (wet, dry, or otherwise) and vice versa.

My thoughts – could be wrong!

Jarren – sorry – just re-read your comments and saw that you were specifying annuals and biennials. I still stick with my original reply, but I do think your point is stronger with those short-lived plants. As you say, disturbance is key. Both good and bad plants have varying requirements for disturbance regimes that favor them. Windows of opportunity for “invasion” or recruitment may close faster in the east, following disturbance. Whether that means it happens less easily, I don’t know. And I still think some plants will be suited for invading wet areas – even short-lived plants.

Pingback: Categorizing Invasive Plants | The Prairie Ecologist

Ok, I think I see the problem. You need to be attending to your weeds, but you’d rather be out photographing. Kidding!

But seriously, I cannot make myself ignore sweetclover in my SE Kansas tallgrass prairie restoration. To me, it looks for all the world to be a nasty invasive. I’m in a battle to the death, and given my ever increasing age it appears I’m the one who’s going to die first. Sweetclover is one of my two great nemeses, the other — even worse — being sericea lespedeza. Between the two I spend scores of days every year in interdiction, even though my wannabe prairie is quite small. That’s a large chunk of my life I’ll never get back.

The sweetclover and lespedeza came with the place, a cow burnt pasture with lots of weeds and some relic natives when I bought it in 1998. An utter novice at the time, I did not know what I had — good or bad. So I was blissfully unaware of these two nasties for the first few years as I commenced my new project. They were happy to be set free from the incessant grazing, and were oh so pleased with their new owner.

Oh, yes, I burned! Who can resist? And the nonnative legumes loved it! I do not know how different things would be today had I not fumbled the handoff from the cows to me, but the regret is profound.

So now I have an enormous, robust soil seed bank that could persist for decades. It is, truly, a contest to see if the weeds can outlast me. I have a policy of “no new seeds.” None. It’s a high bar. Every year I kill every last one of them — or so I hope, perhaps not very realistically. Every year a new throng emerges, counting on me to overlook a couple of them and reset the clock.

Is this driven, compulsive, insanity? I fear that it is. Everybody who knows me thinks I’m crazy.

But how is it possible to look away, or even do this halfway? It seems the only approach is all or nothing, and nothing means walking away and never looking back.

Anyway, to the point of your blog post. I have always believed sweetclover the be aggressive and invasive (I assume I’ll get no quibble from anybody about lespedeza), and everything I can see suggests that it is. It is a force to behold in the roadsides around here. Yes, I know, a roadside is not a prairie. And yes, I know, my immature restoration is not a prairie either. Maybe a real prairie would hold its own, but I don’t think I’d do the experiment even if I had a real prairie at my disposal. It would be too terrifying.

Maybe you are right. Maybe it just depends on the site, or the region, or whatever. But I have seen too many weeds, even minor annuals, increase year over year due to my necessary neglect while concentrating on more existentially important invaders. I have too many times contemplated the reality of inexorable exponential growth. And then there’s this:

Eight or ten years ago I took a quick trip to South Dakota. On the way there I drove through Oglala National Grassland (Nebraska). The hills were golden with yellow sweetclover as far as the eye could see. It was disheartening, sickening. Like my local roadsides, but on a vast landscape scale. I know appearances can be deceiving, and I didn’t get out to check the actual weed density, but that sweetclover sure as heck looked to be the dominant vegetation. In a “national grassland,” no less.

Yes, sweetclover has been with us for some centuries now. It was apparently introduced to North America in the early to mid 1700s. Native Americans were quite familiar with it. So perhaps it has become “naturalized” in some areas and we may as well accept it as the new normal. But I can’t. I just can’t.

Mike, I have a Facebook page called Invasive Plants Cape Breton. We are an island facing many invasives with zero government support and a low population, so we haven’t a chance without education. You write so eloquently of the things I think about and feel as I spend virtually all of my spare time trying to “spare” the native plants and the uniqueness of this biome. A huge part of our economy relies on people coming here to admire the “natural” landscape. Ironically, they love the green and know nothing about it…can’t put their fingers on it, lol. May I please share the above comment on my site? We have sweet clover, and the people trying to save the honeybee don’t understand the whole idea of a “super pollinator” where an invasive makes the job of a bee easier and fewer natives are pollinated. We also have these 9′ plants obliterating views of the water and presenting ugly black skeletons in the fall, when we hope to bring people here to look at our fall colours. Thank you very much for your consideration. I and my husband are getting older and our efforts have to become less physical. Your comments are spot-on.

Yes, of course. Thanks, and good luck.

Pingback: So Similar, Yet So Different | The Prairie Ecologist

Pingback: Making Smart Assumptions about Prairie Management | The Prairie Ecologist

Pingback: One Gardener’s Weed… or Cover Crop? | Gardening in a Drought

I can’t speak to prairies, but in my garden the clover plants are deep rooted monsters that grow incredibly fast and strong and try to crowd all of my other flowers out! I have to aggressively dig them out every time I see them!

Chris, I’d take a look at the following article on how CCB’s here in Iowa are battling sweet clover in Loess Hills prairies in western Iowa:

http://www.pottcoconservation.com/blog/?p=2720

It gets pretty bad out here in Iowa, and I’m currently working with a CRP landowner who unfortunately had it explode in his field after trying to convert it from a grass-dominant to a pollinator habitat seeding. The site was a hayfield decades back, but after repeated disking and burning to prep for the cover conversion, the sweet clover came back (from being pulled up via disking) in mass numbers and created >50% canopy cover over the native seedlings in many if not most places in the field. We had it mowed a couple times last year and thankfully the native seedlings were able to get through and flower out (though they ended up being dwarfed due to mowing, which isn’t a big deal), but we still have another year of work before we’ve killed the second-year growth. Sweet clover is fire-assisted, so burning without any post-burn defoliation to prevent flowering just makes it spread more. However, these guys here in western Iowa used fire to their advantage by burning to stimulate the seed germination and second-year regrowth, and then they mowed the daylights out of it. They repeated this process for 6 years and the results are phenomenal. Granted, this is not something one should do on CRP ground without due approval from USDA (since it removes cover during the primary nesting season).

I will note that sweet clover is one of our oldest introduced species, dating back to the Colonial era or earlier, so it’s practically naturalized, though very few indigenous plants appear to be able to compete with it when it’s at high abundances. It’s wonderful for pollinators, upland game birds, and some other wildlife, but unfortunately, at least here in Iowa and esp. on more mesic soils, it’s a bit of a problem and competes well against the natives. I’d say that sweet clover is perhaps most problematic in reconstructions, esp. those first 3-5 years after seeding, because we’re building the native seedbank from scratch vs. on remnants where there’s a rich seedbank, meaning on the latter we can burn+cut more frequently and might not have significant negative impacts to the stuff we’re wanting to encourage.

Just my two cents.

Learned a lot very informative. I was going to do something stupid. And grow this stuff it would have taken over. In hurricane area. Need to sell this to a farmer up north . It’s sad I wanted to help the bee’s. Thanks for your invested time.