From Anne Stine, Hubbard Fellow:

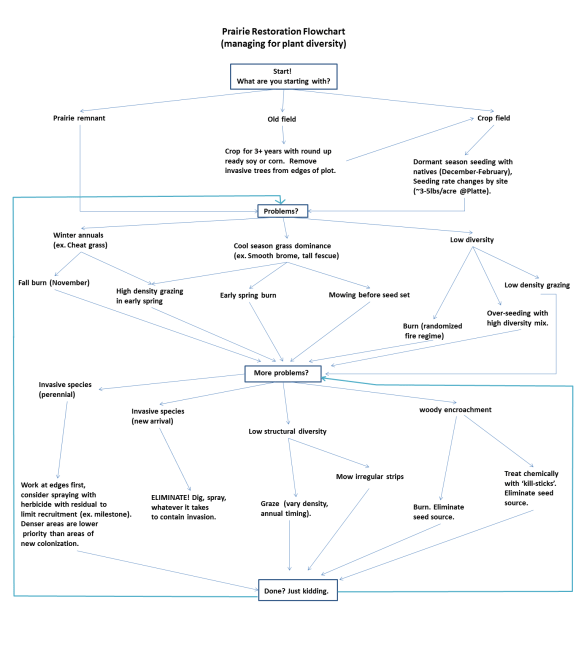

My big goal for this fellowship is to learn how to make a prairie from scratch. I also want to know enough about prairie restoration/management that I can evaluate a prairie’s condition and then prescribe treatments to fix it. For these first few months with The Nature Conservancy, and especially at the Grassland Restoration Network workshop (July 16-18, 2013 in Columbia, MO), I’ve been asking questions about the problems and solutions common to prairie restorations. My naïve desire is to develop some sort of prairie restoration cookbook. When I asked Chris why this didn’t exist, he laughed and said “If that were possible my book would’ve been a lot shorter.” I built my flowchart anyway.

This blog post will be a bit different- I’m going to share the “Patch-Burn Grazing Flowchart” I developed. Then Chris will respond and explain why the cookbook method doesn’t work.

(Click on the flowchart to see it as a larger image)

Response from Chris:

Response from Chris:

I give Anne credit – it’s clear she’s paying attention and learning a lot during the first couple months of her Fellowship experience. Her flow chart includes very appropriate treatments for issues that pop up in prairies, and it’s a nice guide to some of those options. However, prairie restoration and management is a more complex and dynamic process than can be easily captured in a flowchart (or even in a book). That complexity can seem daunting to some, but is really what makes prairies fun and interesting to work with. The trick is to accept the complexity and roll with it.

I’ve been working to rejuvenate our family’s prairie south of Aurora, Nebraska for well over a decade. It’s getting there, but it’s been anything but a straightforward process. Every year brings new challenges and surprises, and we continue to tweak our management strategies.

When I wrote my book on managing prairies, I purposefully stayed away from prescribing any particular management regime (or recipe), and instead tried to provide some background on how prairies work and some guiding principles for managing them. You can find a partial compilation of those ideas by going to PrairieNebraska.org and clicking on the “Prairie Management” or “Prairie Restoration” tabs at the top of the page. There are lots of reasons I didn’t prescribe particular management recipes. Here are a few of them:

1. Every prairie has its own unique species composition (plants, insects, animals, fungi) and that composition drives the way it responds to weather and management. In some ways, prairie management is like parenting – each prairie (and child) has its own personality and needs to be treated in ways that match that personality. The best parenting books are the ones that suggest general philosophies and offer tips to try in various situations. Anyone who has been a parent knows that there is no cookbook for how to do it well.

2. Every year is different. Last year was the driest on record for our Platte River Prairies. This spring was very cool and wet, followed by a hot dry July, followed by a cool and wet August (so far). Prairies respond very differently to fire, grazing, seeding, herbicide treatments, and other techniques due to weather conditions. Countless times, we’ve applied a treatment to part of a prairie and were excited to see how it worked. The next year, we applied the treatment in exactly the same way and things would turn out very differently. We try to tailor our management and restoration to the weather, but we know we’ll be surprised by how things turn out. Those surprises are what I look forward to most each year.

During the drought of 2012 this sandhill prairie was burned and grazed pretty intensively. By late summer, it was looking pretty tough. The same burn timing and grazing stocking rate in a wet year would have resulted in a very different impact.

After adjusting our management plans to account for last year’s drought and grazing, the same sandhill prairie shown above was grazed briefly this spring and – thanks to some good spring rains – looked lush and green by early June.

3. Prairie restoration is not very predictable either. We have developed and tested seeding rates, seeding methods, site preparation, and other techniques that seem to work well at our particular sites, but those same techniques wouldn’t necessarily work somewhere else. One of the big pieces of advice shared each year at Grassland Restoration Network workshops is that when starting a large restoration project, the best plan is to spend several years experimenting with various techniques on small portions of the overall restoration site to figure out what works best at that particular location. Once you figure out what seems to work best, start planting larger and larger areas each year.

However, even when the exact same techniques are applied, results can still vary from year to year. Jeb Barzen and Richard Beilfuss did a great experiment at the International Crane Foundation in the early 1990’s in which they seeded 1 acre a year for five years, using the same seed mix and the same techniques. Even though all the seedings were in the same crop field, each turned out very differently from each other. The same thing happens everywhere. Differences are partially tied to the rainfall and other weather that occurs in the early stages of the seeding, but there are many more factors that are difficult to understand or control. This isn’t a bad thing, it just means that you have to relax your expectations a bit, and embrace the idea of variability. Why would you want to create multiple prairie plantings that look exactly the same as each other anyway?

4. Invasive species are always a major challenge, and (you’ll not be surprised at this) have to be handled in unique ways depending upon the species and the site. Every invasive species has its own growth and reproductive strategies, so an approach to controlling one won’t work well on others. There are general approaches to controlling each species that have been tested and can be useful, but those approaches will work differently from year to year and from site to site. One of most important aspects of invasive species control is prioritization, something Anne’s flowchart covers pretty well, and more information on that can be found here.

5. Finally, one of my guiding principles for prairie management is that diverse prairies require diverse management. Doing the same thing every year means always favoring the same group of species – and, by default, managing against another group. Eventually, that kind of repetitive management can reduce overall species diversity by eliminating plants or animals that can’t thrive under that management. It’s good to mix things up to allow all the species in a prairie to have a good productive year now and then.

If a prairie is large enough, splitting it into multiple management units each year can help ensure that animals and insects can always find what they need for habitat (it’s more difficult to do that in very small prairies). However, it’s also important to avoid simply splitting a prairie into the same three or four pieces and rotating management between them in a repetitive pattern – even those patterns can restrict species diversity over time.

Many prairie insects and animals have fairly specific habitat needs. Grasshoppers, for example, tend to thrive best in areas with patchy vegetation structure that allows them to move easily back and forth between shade and sun. Splitting prairie into multiple management units each year can help provide a variety of habitat conditions and maintain high species diversity.

During the next couple of months, Anne and Eliza will be part of our annual management planning process here in the Platte River Prairies. Each fall, we go around to each of our prairies and go through a basic evaluation process. How does the prairie look this year? What were the impacts of weather and management this year? What challenges, including invasive species, are we facing? What kinds of management have occurred over the last several years? What does the monitoring data from the last couple of years tell us about how past management has been working (sometimes we have hard data, but we always have field notes and other observations to consider).

We walk around, look at maps, and talk about ideas. Then we sketch out a plan for the next season based on all of those factors. We try to make sure it’s different from what we’ve done over the last year or two, but that it addresses the challenges the prairie is facing. Most importantly, we make sure that we’re learning from and adapting to what we’ve tried in the past and the ways the prairie has responded.

I suppose I could capture that process in a flowchart. It would look something like this:

That’s probably not exactly what Anne was hoping for, is it?