I don’t know about you, but a nice quiet walk through the prairie can often help me deal with everything else going on around me. Last weekend, I spent parts of both Saturday and Sunday cutting trees and fixing fence at our family prairie. I also wandered around a fair amount and, as always, found things to stir my curiosity and wonder.

Many of us don’t need added incentives to draw us outside, but that doesn’t mean incentives can’t help. Or, maybe you have friends or relatives who aren’t sure what they’d even do or look for in a prairie, especially this time of year. After all, isn’t it all just a bunch of brown grass out there right now?

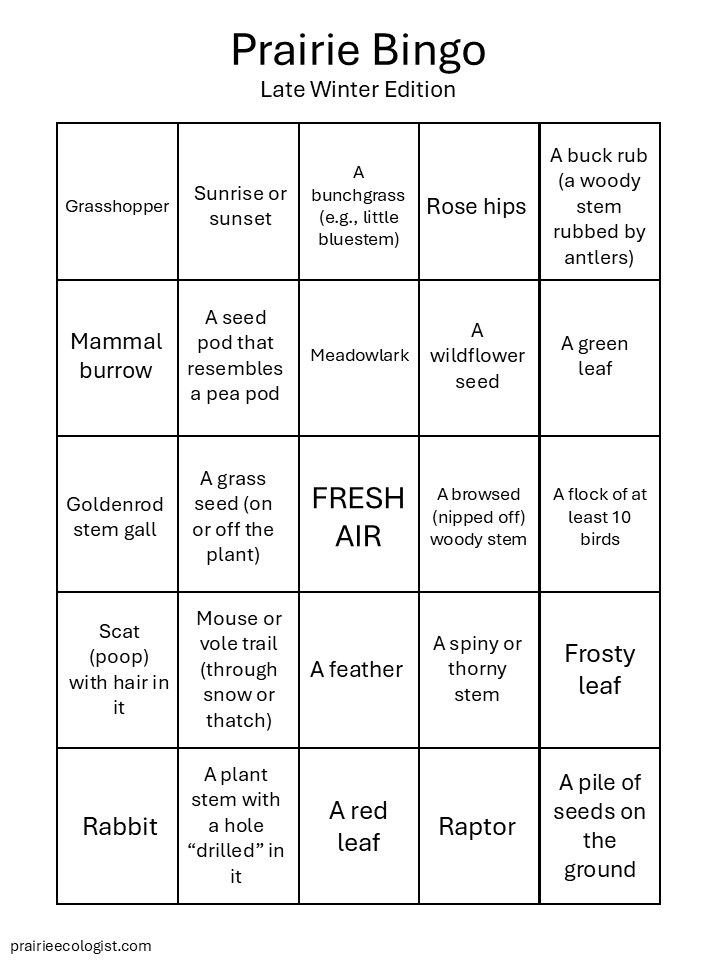

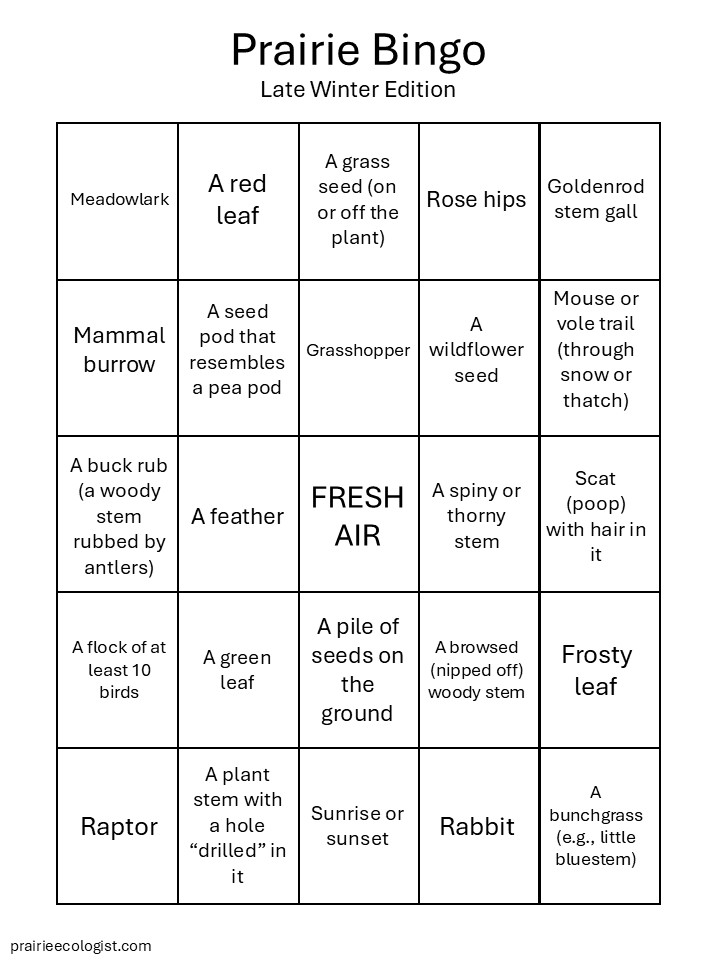

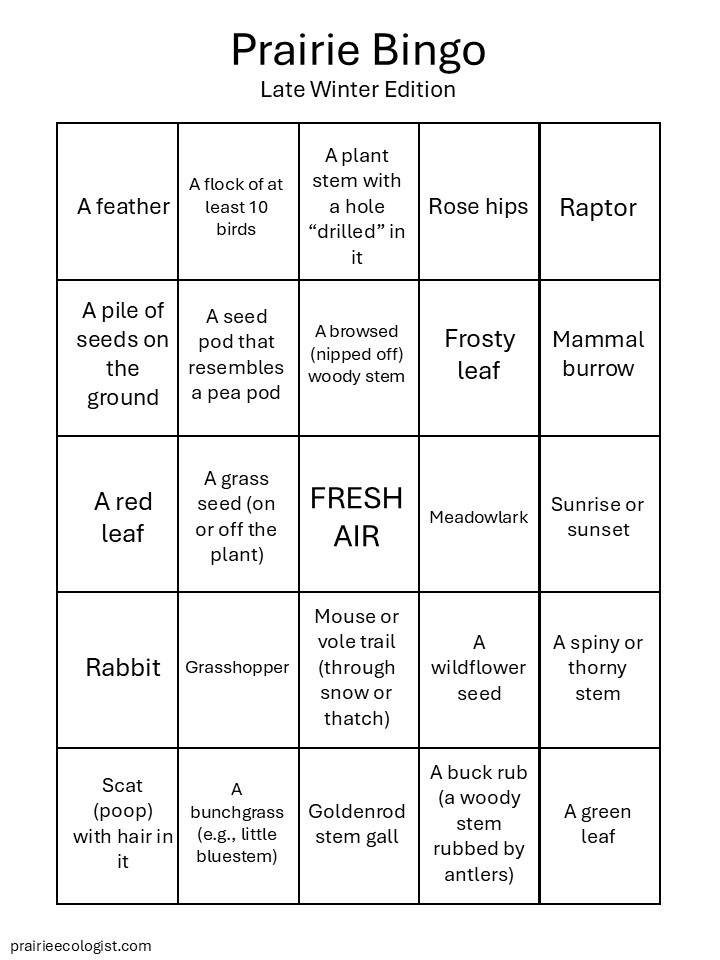

Well, if it’s at all helpful, I’ve created a prairie bingo card. If you just let out an exasperated sigh when you read that sentence, that’s fine. This isn’t for you. No offense taken.

If you are still reading this, maybe you’d find it fun to add a little extra twist to your next trip to a local prairie. Maybe you have some friends who would come play a game with you but wouldn’t otherwise consider going for a prairie hike. I don’t know your situation.

I tried to create a bingo card that would be accessible to just about anyone. Anything that might be unfamiliar should be easy to quickly find an explanation of online. Everything on the card is something I’ve seen in the last couple weeks during walks in prairies near here.

If this looks like fun, feel free to save or print the bingo card. Or just make your own, using this one as inspiration. If you plan to go out with friends and don’t want to all use the same card, I’ve made two more versions (below) with the same terms but in different arrangements.

If you decide to try this, I’d love to hear what you think. Whether you play prairie bingo or not, though, I hope you find some time to go exploring. Even in the late winter, there’s plenty to see out there!