As I wrap up my square meter photography project (May 4 will be the last day of the 2024-2025 edition), I’ve been thinking about what I want to do next. The other day, I came up with an idea and I’m jumping in with both feet. I think it’ll be fun and informative, but I’m telling you about it now because that will help me stick with it. (I can’t very well back out now, can I? I just committed to it in front of thousands of people.)

I spend a lot of my time thinking up ways to create a shifting mosaic of habitats in prairies. It’s an approach that has been shown to sustain biodiversity and ecological resilience and, if you’re not familiar with it, you can read more about it here.

One of the key components of our particular shifting mosaic approaches is that individual patches of prairie often get a prolonged period of pretty intense grazing (usual a full season, give or take) and then an even longer rest period. To me, the most fascinating portion of that cycle is the first growing season following a long grazing period.

Following a full season of grazing, most of the perennial vegetation has reduced vigor because it was repeatedly cropped by cattle throughout the previous season. That opens up space for other plants who normally can’t compete well with those perennials. The result is a wild party of annuals, biennials, and other opportunistic plants until those perennials regain their full strength. It’s a fun, unpredictable, messy mix of plant species and habitat conditions.

Messiness and unpredictability can make a lot of grassland managers uncomfortable. This is true for prairie managers working for conservation organizations as well as for private landowners. I understand the discomfort, but I also feel like a lot of that comes from a distrust of the resilience of prairies. Especially in larger prairies (those bigger than, say, 80-100 acres or so), I think there’s value in putting prairies through their paces a little. Our grazing/rest cycles provide a wide variety of habitat for animals, but also help ensure all the members of the plant community get a chance to thrive and express themselves periodically.

Anyway, to draw attention to the fun, unpredictable, messiness of post-grazing prairies, I’m starting a new photography project this year. I’ll be observing and photographing portions of three prairies managed with a shifting mosaic approach that includes long periods of intense grazing and long periods of rest. In particular, I’m going to illustrate what happens during the first growing season after that grazing ends. I’ll spend most of my time within an 80×80 foot square marked out at each of those three sites.

I’m going to introduce two of the three project sites today. The third site is laid out, but I haven’t had time to photograph there yet.

The first site is within a restored prairie at The Nature Conservancy’s Platte River Prairies that I planted in 2000 with 202 plant species. It’s been managed with various shifting mosaic grazing approaches since about 2009, including patch-burn grazing and others. Plant diversity has remained very steady over that time period.

Last summer, Preserve Manager Cody Miller had the center of the prairie hayed in mid-June. The cattle in the prairie then spent the majority of their time in that hayed patch, keeping it cropped short to the ground through the end of the growing season. It’s very similar to patch-burn grazing, but the focal grazing was driven by haying instead of fire.

When I set up my photo plot earlier this week, the vegetation was very short and there was a lot of dried manure scattered across the prairie. To many people, it probably looks like an ecological disaster, but I’m excited to see what happens this year. There are already some hints (see photos below) of some of the wildflowers that will thrive in the absence of strong competition from typically-dominant grasses and other plants.

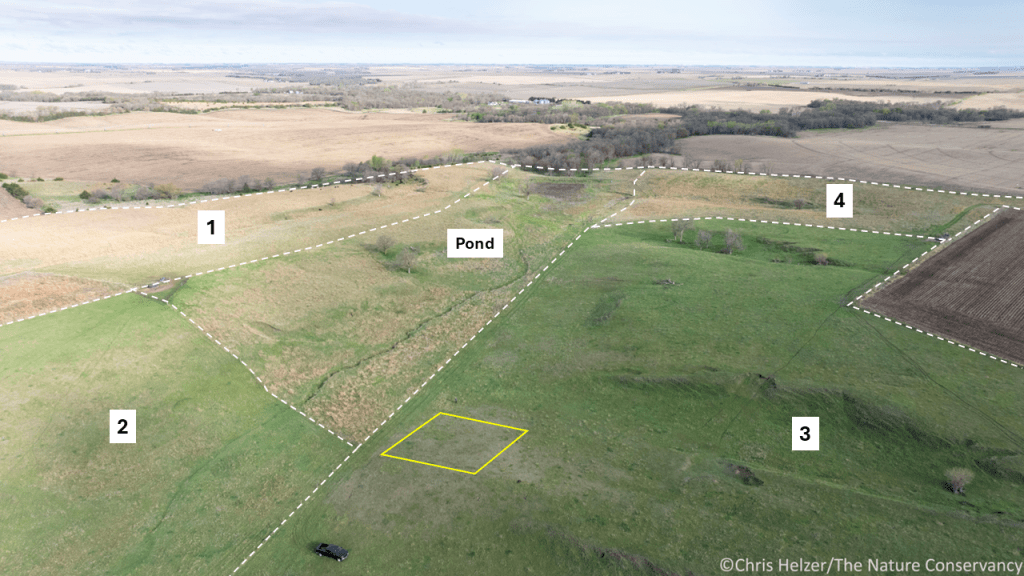

The second of my three focal sites this year is my family prairie. The prairie is a combination of scattered small parcels of unplowed prairie surrounded by former cropland that was planted to grass in the early 1960’s. I’ve located my photo plot in what I’m pretty sure is an unplowed portion of the site. I’m using both old aerial photos and current vegetation composition to make that educated guess.

My 80×80 photo plot sits on a gentle northwest-facing slope within a pasture (#3) that was heavily grazed all last year. It’s part of an open-gate rotational system, so a gate was opened to a second pasture in the mid-summer, but cattle still focused most of their attention on pasture #3. That is evident in the very short vegetation structure and abundant bare ground in the photos I took yesterday (May 1). It is poised for a very interesting growing season.

As with the West Derr restoration, the plot at my family prairie has some early indications of the plants that will have a good year in this post-grazing season. It also has a stronger community of early season wildflowers than the restored prairie. I photographed some of those when I was at the site yesterday. They were easy to see because of the short habitat structure, and many were either more abundant, bloomed earlier, or both, than their peers in the ungrazed areas of the same prairie.

I’ll share photos of the third site soon. It’s part of a 1995 prairie restoration at the Platte River Prairies that’s managed a very similar open-gate rotational grazing as I use at my family prairie.

My hope is that this project will help others see what I like about the wild and crazy post-grazing period in prairies. I don’t know what will happen in these plots – that’s part of the fun! I hope you’ll enjoy tagging along with me as I watch them.