Hi everyone. The following blog post is written by 2024 Hubbard Fellow Claire Morrical. Claire put together a fantastic series of interviews with people working in conservation here in Nebraska and we thought you’d enjoy reading and listening to their stories.

This project – Perspectives of the Prairie – uses interviews and maps to share the perspectives and stories of people, from ecologists to volunteers, on the prairie. You can check out the full project HERE.

This post also contains audio clips. You can find the text from this blog post with audio transcripts HERE. If you’re reading this post in your email and the audio clips don’t work, click on the title of the post to open it online.

Find the first entry of Perspectives of the Prairie, Neil Dankert HERE

In 2014, Mike began what is now a 10-year survey of small mammals at Platte River Prairies. I joined Mike while he set traps for the evening to talk about the answers and questions that arose from the survey, what the prairie looks like from the small mammal perspective, and how Mike’s career impacts his work today.

Interview: July 11th, 2024

Part 1: Meet Mike

Location: A kangaroo rat burrow in the Derr Sandhills site at Platte River Prairies

This is Mike Schrad.

Three times a year (spring, summer, and fall), Mike drives down to Platte River Prairies and surveys small mammals for two days. In the evenings, he sets up two grids of 40 traps, then returns at dawn to see what he’s caught.

I met up with Mike on a warm July evening and we drive out to the site the Derr Sandhills to set traps. Like the more expansive Nebraska Sandhills to the north, our little sandhills are made up of rolling grass-covered dunes, with sand-loving species like little bluestem and the aptly named sand lovegrass.

We meander up and down the rows, searching for Sherman traps (picture 2) to refill with seed for tomorrow’s critters. By the morning, a furry little creature will have wandered into the long metal box, looking for food, and a door will snap shut, trapping it until it’s found, measured, and then released back into the prairie.

Mike Schrad is a retired wildlife biologist who has volunteered at Platte River Prairies for the last 10 years. Mike collects small mammal data on this site, helping us to understand the creatures that use it and how our management affects them.

As he works, Mike is quick to point out what he notices.

Notes for Context:

- Chris Helzer: Director of Science and Stewardship for Nebraska TNC. Chris has spent much of his career at Platte River Prairies

- Hall County: The Nebraska county where Platte River Prairies is located

- The Natural Legacy Project: Works to identify and protect at risk, state threatened, and state endangered species in Nebraska (referred to as the Legacy Program by Mike)

In March of 2024, the Ord’s Kangaroo Rat, or the k-rat, was officially recorded on Platte River Prairies for the first time. K-rats are well-named, balancing on strong hind legs and hopping through tall grasses like very little kangaroos (though still bigger than the small mammals Mike aims to catch in his traps). You can tell a kangaroo rat is present by the long s curves its tail leaves in the sand around its burrow entrance.

Mikes career as a wildlife biologist continues to inform his perspective and his work on our sandhills, providing the preserve with a better understanding of what is in our prairie. In turn, Mike has learned a lot himself and finds that he is more confident in the next generation of ecologists.

Part 2: Surveying Small Mammals

Location: The site East Dahms at Platte River Prairies where the original small mammal survey was done

What started as a one-time survey has grown into a project that spans ten years and has recorded over 450 small mammals. As we set traps, Mike tells us how it all started.

Notes for Context:

- Chris Helzer: Director of Science and Stewardship for Nebraska TNC. Chris has spent much of his career at Platte River Prairies

- The Natural Legacy Project: Works to identify and protect at risk, state threatened, and state endangered species in Nebraska (referred to as the Legacy Program by Mike)

Small Mammals Mentioned: Plains pocket mouse (Perognathus flavescens)

What this study gives us is an understanding of what small mammal species are using our the Derr Sandhills. Of them, Mike is particularly interested in the plains pocket mouse. Perhaps most notable for its fur lined cheek pouches (or pockets, if you will), the pocket mouse feeds mainly on seeds which they can store in their pouches, and later in seed caches separate from their nest burrows.

Plains pocket mice can be divided into two subspecies, an eastern and a western subspecies, which can be told apart by slight differences in their fur color. Of the two, the eastern plains pocket mouse is less common, and is listed as a tier one species in the Nebraska Natural Legacy Project.

One of our past Hubbard fellows, Jasmine Cutter, has a great piece about the plains pocket mouse HERE.

Notes for Context:

- Dr. Keith Geluso: Professor of Biology at the University of Nebraska Kearney

- Tier One Species: Species most at risk for extinction

Small Mammals Mentioned: Prairie Vole (Microtus ochrogaster), White-footed mouse (Peromyscus leucopus), Deer Mouse (Peromyscus maniculatus), Plains Pocket Mouse (Perognathus flavescens), Hispid Pocket Mouse (Chactodipus hispidus), Northern Grasshopper Mouse (Onychomys leucogaster)

Northern grasshopper mice ARE really neat. They’re territorial animals, and unlike a majority of mouse species, grasshopper mice are carnivorous, eating mainly insects. In addition to being a terrifying predator (if you’re a grasshopper), grasshopper mice are known for their howl. The mice will throw back their head and let out a high-pitched whistle.

Mike and the Platte River Prairies team have an idea of what’s here, but that’s just the beginning of the story. To start, Mike needs enough data to prove that his findings are accurate. In the meantime, what we’ve ended up with is a door that’s been opened to a whole lot of questions that take their own research to answer.

One example of research that’s stemmed from Mike’s work is a research project by a past Hubbard fellow, Jasmine Cutter.

Mike shares another example with us.

Notes for Context:

- Pit tags: a microchip that can be planted under the skin of an animal, allowing us to track where the animal is at using GPS.

Small Mammals Mentioned: Deer Mouse (Peromyscus maniculatus), Plains Pocket Mouse (Perognathus flavescens)

Part 3: Restored Prairie

Location: The restored portion of the Derr Sandhills site at Platte River Prairies

The Derr Sandhills is made up of both restored and remnant prairie. Remnant prairie has never been plowed and never existed as something other than grassland (at least in the last several hundred years). It may be beaten up, over-grazed, overwhelmed with invasive species, but it has always been prairie.

Restored prairie on the other hand, has been fundamentally changed into something that isn’t prairie. In this case, a corn field. As a result, the seed bank is lost, soil nutrients and hydrology may change, and the prairie cannot return to exactly what it was before. That doesn’t mean it can’t be restored to a great prairie. As Mike Schrad will tell you, it’s just different.

This site was restored in 2001. Here at the restored site, the grass is taller and thicker. On much of it, you have to dig through a quarter inch of old grass to get to the soil. So, what have we found on this restored site?

Small mammals mentioned: Plains Pocket Mouse (Perognathus flavescens), Deer Mouse (Peromyscus maniculatus)

“Why?” is a question Mike asks often.

Part 4: Remnant Prairie

Location: The remnant portion of the Derr Sandhills site at Platte River Prairies

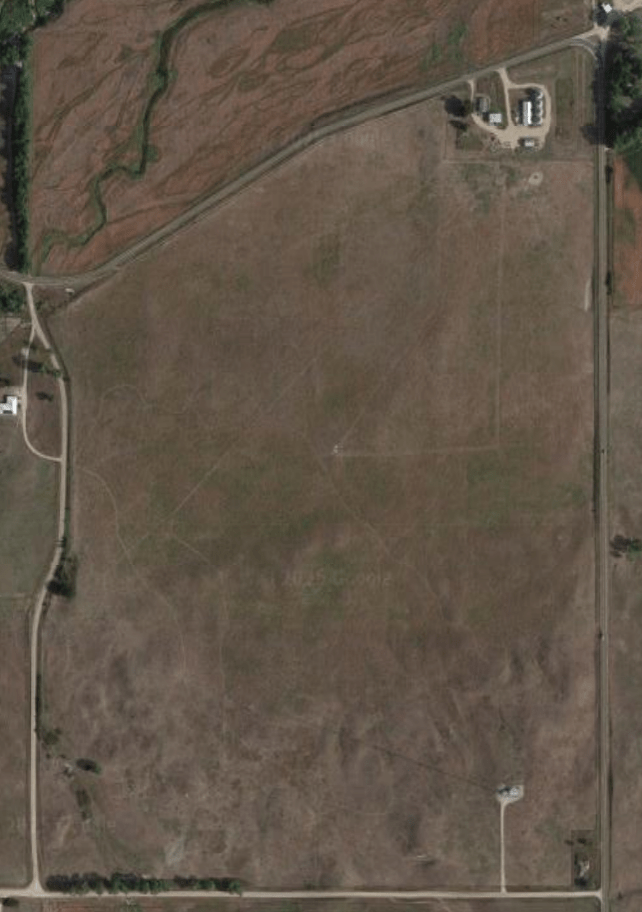

If you look at a satellite image of the Derr Sandhills, you can just make out where the old crop field was and the circle that an old pivot irrigator once drew around the edge of it. To the south of the restored sandhills is the remnant sandhills, noticeably hillier, and as Mike says, “just different”.

Google and Google Docs are trademarks of Google LLC and this book is not endorsed by or affiliated with Google in any way.

Notes for Context:

- Remnant Prairie: Prairie that has never been plowed

- Restored Prairie: Prairie that was plowed (for example, for cropland or housing development), but later replanted back into a prairie

Mike and I stood in the remnant prairie, overlooking the restored portion. There is a line just visible between the two sections where the community of plant species changes. From the Indiangrass and big bluestem in the restored prairie to the sand lovegrass and little bluestem in the remnant, the two different plant compositions complement each other both visually and ecologically. Research by previous Hubbard fellow, Anne Stine, showed native bees using both parts of the prairie as they hunted for pollen.

Mike compares the restored, where the vegetation was taller and thicker, to the remnant.

Notes for Context: We use cattle grazing as a management tool on our prairies. Cattle can be a great substitute for bison, adding disturbance to the prairie and helping us manage our invasive species. Mike refers cattle’s role in creating different vegetation structures (like tall and dense or short and sparse) across the prairie. Our goal is to have a variety of vegetation structures (which we call “habitat heterogeneity”) so that the prairie can host many different species with different needs.

This summer, the Derr Sandhills were grazed for the first time in several years.

- Chris Helzer: Director of Science and Stewardship for Nebraska TNC. Chris has spent much of his career at Platte River Prairies

Mike shares some of his findings from the sandhills and how they just keep raising more questions.

Part 5: From a Mouse’s Point of View

Location: The Derr Sandhills

This is what Mike notices in the prairie –

These mosaics that Mike points out are areas of patchwork structure. Some tall grasses with dense thatch, some sparser grass with bare ground below it, some bare sandy mounds, pushed up by pocket gophers as they tunnel underground.

Mike is a strong supporter of seeing from the perspective of his small mammals and encourages others to do the same. Looking through the eyes of a small mammal, these mosaics can make a big difference. It affects how easy it is to move, to hide, to stay warm.

Just like people, other animals need different types of spaces. Places where they feel safe, places they can find food. And just like different people have their preferences, so do small mammals. By having diverse habitat across our prairies, we can make sure more species have the habitat and structure they like.

Small mammals Mentioned: Western Harvest Mouse (Reithrodontomys magalotis), Prairie Vole (Microtus ochrogaster)

Unlike grasshopper mice, western harvest mice (R. magalotis) are quite tolerant of their neighbors. Like Mike says, they often nest above ground, such as at the base of clumps of grass.

Prairie voles can be distinguished from the other critters Mike captures by their stout snout and short tails.

Even with an eye to the ground, small mammals can surprise Mike.

Small Mammals Mentioned: Plains Pocket Mouse (Perognathus flavescens)

Part 6: Strip Mines and Sandhills

Location: the site Dahms East at Platte River Prairies, where we use open gate grazing

You might remember this clip from the beginning of Mike’s interview –

That experience continues to shape Mike’s perspective during his volunteer work at Platte River Prairies and of the value of his research.

In his old career, Mike was thinking about how human activity that drastically changed the landscape, would impact animal species, and what could be done to make sure those species persisted in spite of these huge disturbances.

Notes for Context: Mike talks about sage grouse strutting grounds. Also known as leks, these are areas where male grouse gather to perform for females. They inflate and deflate sacks of air, making a bubble-like sound in an unending display in hopes a hen will choose to mate with him. Grouse can be extremely dedicated to a lek site, returning to the same site year after year. Learn more HERE.

Recreating a landscape after mining and watching a prairie after a season of heavy grazing may seem vastly different, but the comparison is clear to Mike. We are still changing the landscape and how we go about doing that affects which critters will thrive here.

Notes for Context:

- Chris Helzer: Director of Science and Stewardship for Nebraska TNC. Chris has spent much of his career at Platte River Prairies

- Brome Grass: A genus of grass, many of which are invasive to Nebraska

On a site that hasn’t seen much disturbance in the last several years, Mike is excited to see what the coming grazing will bring, although he hopes to avoid the inconveniences.

Notes for Context: Mike refers to a new grazing technique. This technique is called “open gate grazing” and is a way for us to create that habitat heterogeneity that will allow many different species to thrive here. You can learn how this grazing system works HERE.

- Cody Miller: Preserve manager at Platte River Prairies