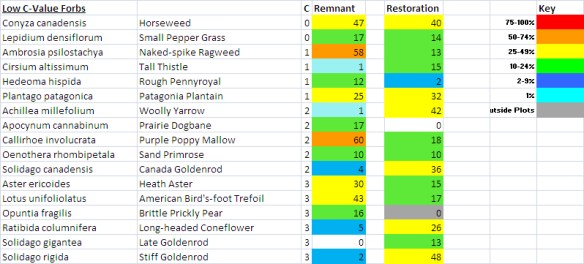

In many prairies, the primary suppressors of plant diversity are dominant grasses – both native and non-native. These grasses, left unchecked, can monopolize light, moisture, and nutrients to the point that few other plant species can coexist with them. I’m not sure why some prairies suffer from this more than others. There is some evidence that hemi-parasitic and allelopathic plants such as pussy toes, false toadflax, and wood betony can play a role in suppressing grasses and facilitating forb diversity, but I don’t think that’s the whole answer because I’ve seen very diverse prairie plant communities without those species – or with only a few scattered populations of them. Regardless of the reasons, we are left with many prairies that have lost – or are losing – plant diversity through domination by grasses, and we have to decide what to do with them. Some of those prairies are restored (reconstructed) prairies that started out with high plant diversity but have since lost much of that diversity. Others are remnant prairies that have been degraded by overgrazing and/or broadcast herbicide application. Still others are relatively diverse remnant prairies that are slowly losing diversity as individual forbs die without reproducing.

I think one of the best tools we have for combating grass domination in prairies is defoliation – the removal of above-ground portions of plants. Defoliation has always been a major component of prairie ecosystems through fire and herbivory, and mowing and (non-lethal “burn back”) herbicide applications are additional options at our disposal today. Plants respond to defoliation in various ways, depending upon the severity of defoliation, the frequency and/or duration of the defoliating event, the stage of the plant’s growth at the time of defoliation, and each species’ genetic programming. The way each plant, and its neighbors, respond to a defoliation event determines which plants will gain or lose territory. In other words, defoliation influences the competition between plants – and manipulating competition between plants is really what most prairie management is all about.

Some of the earliest research I’m aware of on the effects of prairie plant defoliation can be found in range management research from the 1950’s and 1960’s. The earliest paper that is often cited from that era is by F.J. Crider, who documented the effects of defoliation on the root growth of grasses. He (and others since) found that a severe defoliation of a grass plant resulted in an immediate cessation of root growth as plants reallocated resources from root growth to regrow leaves and stems. More importantly, those grass plants actually abandoned sections of living roots as well – shrinking the total root mass of the plant fairly dramatically. This makes sense, since the plant has to support those roots through photosynthesis, and a severe defoliation takes away most of the plant’s ability to photosynthesize.

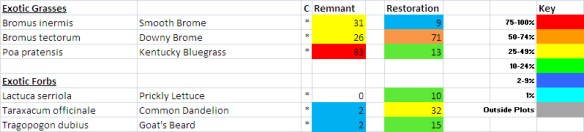

A simplified look at how dominant grasses can affect plant diversity. In the top example (A) grasses have monopolized both aboveground (light) and belowground resources (moisture and nutrients). After defoliation (B), both the above and belowground parts of the grasses have shrunk, freeing up resources and allowing other plants to establish within that lost territory. As the grasses recover from the stress of defoliation, their vigor and size increase, but the new plants have a fighting chance - at least for a while - to hold the new ground they've taken.

Those early range science research data provide some useful context for today’s prairie management, but those researchers were primarily trying to figure out the intensity of grazing they could employ while still maintaining a dominant stand of grass. As prairie managers, by contrast, we want to reduce the dominance of grass to increase the diversity of other plants. We can still learn from what those range scientists discovered; we just want to employ it in a different way. Since plants primarily compete for light, moisture, and nutrients, we want to find ways to make those three kinds of resources more available to plants other than dominant grasses. Defoliation can reduce shading aboveground (removal of leaves and stems), while simultaneously freeing up the availability of moisture and nutrients belowground (reduction of root masses).

In prairies where dominant grass species are suppressing plant diversity, we want to defoliate those grasses in a way that forces them to cede territory to other species. In order for that to work, the first important factor is that the defoliation has to happen during the growing season. Defoliating a dormant plant (e.g. with an early spring burn) doesn’t have any impact on its root system, which is a critically-important part of its competitive ability. In order to force a plant to reallocate resources away from its roots, defoliation needs to take place after the plant has already invested significant resources in above-ground growth. This is why a late-spring burn can have a significant (if temporary) impact on cool-season exotic grasses such as smooth brome. Burning, grazing, or mowing grasses when they are just starting to flower has the biggest impact on most species because they have invested the maximum amount in their above-ground growth by that point. Alternatively, repetitive mowing or grazing of grasses can also have a strong – and perhaps longer lasting – impact on their root systems because every time the grasses start to regrow, they get nipped off again, forcing them to regroup and reallocate resources time after time.

The immediate result of that kind of severe and/or repeated defoliation of dominant grasses is a release of opportunistic plants that thrive under low levels of competition. This includes many annual and biennial plants, but also perennial plants that are built to move quickly into open space. The quick flush of these plants often turns people off of defoliation because of a widely-held misperception that those “weedy” plants are outcompeting “good” plants. In truth, the weedy plants are only able to grow because the competition that normally holds them in check has been suppressed. When the defoliation event is over, the dominant grasses and other perennial plants will slowly recover their vigor – at which point the weedy plants will retreat and wait for another opportunity. Rather than indicating a problem, I use the presence of weedy plants to tell me that my defoliation treatment has succeeded in weakening dominant grasses and has opened up space for other plants to take advantage of.

As common as the overly-dominant grass problem is in prairie conservation, there is a frustrating scarcity of research that addresses it. However, a recently-published research project by Kat McCain and others at Kansas State University provides some very nice insight into what can happen when dominant grass species are suppressed in a restored (reconstructed) prairie. Kat and her colleagues studied plots of seeded prairie that had become heavily dominated by big bluestem and switchgrass over time. They found that removing half or all of the big bluestem tillers (stems) – by clipping and herbicide application – from a plot significantly increased plant diversity. Interestingly, removing switchgrass tillers in the same way had much less impact. Following the removal of big bluestem tillers, the researchers saw increases in the vegetative cover of some forb species, including roundheaded bushclover (Lespedeza capitata), pitcher sage (Salvia azurea), and blue wild indigo (Baptisia australis) within those plots, as well as new establishment of forb species including whorled milkweed (Asclepias verticillata), green antelopehorn milkweed (Asclepias viridis), leadplant (Amorpha canescens), roundheaded bushclover, and heath aster (Symphyotrichum ericoides). In other words, suppression of big bluestem competition led to increased vigor among existing forbs and also allowed new plants to establish in the territory previously held by the dominant grass. The study bolsters the theory that grass competition is suppressing forb diversity in many prairies, but also provides information on how plant communities might respond if that grass competition is reduced.

Of course there is a difference between simple defoliation and the kind of clipping/herbicide combination used by McCain and her colleagues. In addition, most defoliation treatments (especially prescribed fire and haying) in prairie management are non-selective, meaning that all plants are simultaneously defoliated – not just the ones we want to suppress. Uniform defoliation likely decreases some of the benefits of suppressing grass vigor because the vigor of the plants we hope will respond is suppressed as well. However, there will be still be plants that can take advantage of the newly available light and soil resources following a uniform defoliation treatment, and by altering the timing of defoliations from year to year, we can ensure that a variety of species get the opportunity to respond.

Haying is a good example of uniform defoliation. Every plant gets cut at the same height and at the same time.

Ideally, though, we would like the ability to defoliate only those species that are suppressing plant diversity. One way to do that is by using a selective herbicide such as Poast, which affects only grasses (not forbs, sedges, or other plants). Poast is labeled for control of annual grasses, but at light rates can also provide short-term burn-back (defoliation) of perennial grasses as well, and some prairie managers have seen plant diversity increase following treatments. Because it can kill annual grasses, and calibrating the appropriate application rate with the desired result can be tricky, it’s probably best to use this treatment on restored prairie rather than on remnant prairies for now – and to test it on small patches first.

Another way to get selective defoliation is by the use of grazing. In an earlier post, I described our use of patch-burn grazing in our Platte River Prairies as a way to increase and maintain plant diversity. Patch-burn grazing is essentially a technique that uses patches of burned prairie within a larger prairie to attract grazing animals, concentrating grazing activity in those burned areas while allowing other areas to recover. Under a light stocking rate, we find that cattle – even in the burned patches – are very selective about the plants they choose to eat. Their top choice of grasses in the spring is smooth brome, and their summer favorite is big bluestem. These happen to be two of the top three grasses that appear to stifle plant diversity in our prairies (the third is Kentucky bluegrass, which cattle like less well). In our application of patch-burn grazing, a burned patch of prairie is normally grazed intensively for an entire season before the next patch is burned and cattle shift their attention to that. That length of intense defoliation has significant impacts on the plants that are grazed – and again, under light stocking rates, the primary plants that are defoliated are smooth brome and big bluestem. Interestingly, switchgrass is much less attractive to cattle and is often left ungrazed – or lightly grazed – in our prairies. I found it intriguing (and encouraging!) that McCain and her colleagues found that switchgrass appeared to have much less impact on plant diversity than big bluestem did.

The effects of selective grazing in a restored prairie. This photo shows the burned patch with a patch-burn grazing system where a light stocking rate allows cattle to be selective about their eating preferences. Big bluestem is cropped very short, while other grasses and forbs are ungrazed or lightly grazed. Species such as hoary vervain aren't typically grazed even under high stocking rates, but many species such as purple prairie clover (front left), illinois bundleflower (middle left) and stiff sunflower (blooming) are commonly considered to be favorites of cattle - but only at higher stocking rates.

It would stand to reason that selective grazing of big bluestem and smooth brome would favor the expansion of the ungrazed plant species growing with those grasses. While I’ve not had the time or resources to conduct much full-scale research (help wanted!), I do have data that supports that idea. Through annual data collection of plant species frequency, I’ve found that the density of species (the number of plant species per 1m2 plot) increases by 20 to 30 percent in the year following the burn/graze treatment in a patch of prairie – in both restored and remnant prairies.

Data from two prairies under patch-burn grazing. In both cases, the graphs show the number of plant species per square meter over time from the year of fire and intense grazing through the two subsequent years. The East Dahms site is a degraded remnant prairie and the Dahms 95 site is a restored prairie that was seeded in 1995 with over 150 plant species. The error bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

Of course, the increase I see in species density following grazing includes many plants such as ragweed and other opportunistic species, but I also see species like purple prairie clover (Dalea purpurea), Illinois bundleflower (Desmanthus illinoiensis), and stiff sunflower (Helianthus laetiflorus) respond as well. In addition to seeing this in my plot data, I can walk out into the prairies and see seedlings of these species around the adult ungrazed plants. Not all of those young plants survive their first year or two, but some permanent plot data I’ve looked at shows that at least some of them do. By the way, I see similar post-grazing increases in plant species density and establishment of species like prairie clover under patch-burn grazing with higher stocking rates (less selective grazing) as well.

As I said in my previous post on grazing, I’m not advocating that all prairies need to be grazed. I’m not even advocating grazing as the solution to all prairies that suffer from overly-dominant grasses. However, as we search for answers to address grass suppression of plant diversity, grazing certainly appears to be one viable alternative that is worth more investigation. I’m continuing to experiment with variations in the way we employ fire and grazing treatments, and will keep learning as I go. I’m also combining seed additions with those grazing treatments to see if I can take advantage of the open space created by defoliation to help establish new plants from seed – something that appears to happen rarely without some kind of suppression of surrounding vegetation. I’m seeing some positive results, but it’s too early to know how well it will work long-term, and I’m still tweaking seeding rates and other factors.

Whether it’s grazing, prescribed fire, haying, or herbicide application, defoliation may be the most powerful tool available to help us suppress dominant grasses and increase plant diversity in prairies – where that is an issue. The biggest obstacle to its application is probably the fear of causing damage to prairie by burning, cutting, or grazing plants during the growing season, but I think that fear ignores the resilience of prairie communities. We still have a lot to learn about the most effective ways to apply defoliation to achieve our objectives, but the only way we’ll learn is by experimentation. I hope you’ll join me in testing these methods and tracking the results. If you do, please share what you learn with the rest of us so we can all work to figure this out.