This is a follow-up to last week’s post on using prairie restoration to enlarge and reconnect remnant prairies. In this week’s post, I present a case study of a remnant sand prairie and an adjacent prairie restoration, and give thoughts about how to measure the effectiveness of that restoration project. We’re (all of us) just getting started figuring out how to measure this kind of thing, so I’m hoping my thoughts will stimulate others to come up with their own ideas to improve upon – or contradict – mine.

Last week, I wrote about how we can improve our chances of conservation success in small isolated prairies by using prairie restoration (reconstruction) to enlarge and reconnect prairie fragments. I even made a goofy analogy about catching falling popcorn. At the end, I mentioned that when measuring the success of a prairie restoration – as a tool for enlarging or reconnecting remnants – we need to take a different approach than simply comparing the remnant and restored prairies to see how similar they are. If the point of the restored prairie is to reduce the level of threat to species and natural communities inside the remnant prairie, that’s what we need to measure.

To explain what I mean, let me use a restored/remnant prairie complex along Nebraska’s Platte River as an example. In 2000, The Nature Conservancy added several hundred acres to our Platte River Prairies through a land acquisition. Most of the new land was cropland, but it also included 60 acres of remnant mixed-grass sand prairie with good plant diversity. Two years later, using seed harvested from the remnant prairie and other nearby sites, we seeded 110 acres of cropland directly adjacent to the sand prairie. The restored cropland has the same kind of hilly topography as the remnant, but also includes some low areas more appropriate for mesic tallgrass prairie. Thus, the 162 species in our seed mixture included plant species from both mixed-grass sand prairie and mesic tallgrass prairie.

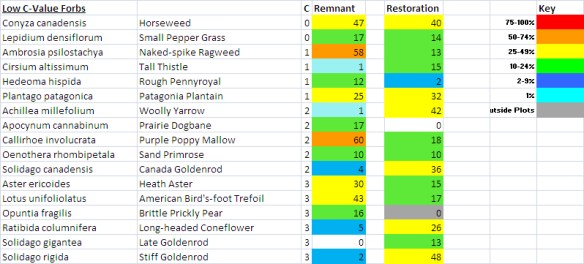

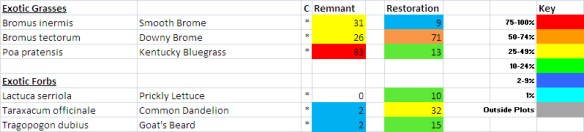

In June of 2010 I collected plant data from both the remnant and restored prairie (in its ninth growing season). The data were collected by counting the plant species inside a 1m2 plot frame from 100 locations across each prairie. Those data allowed me see the frequency of occurrence of each species (the % of plots in which each species was found). To make the results easier for you to visualize, I’ve used a color-coding system to create what I call a plant composition signature for each prairie. The complete comparison of the two prairies, with additional interpretation, can be seen here if you’re interested, but for this example, I’m just going to show some representative excerpts.

After the latin and common name for each species, you’ll see a column labeled “C”, which is the C-value (or coefficient of conservatism – defined by Swink and Wilhelm 1994). If you’re not familiar with this categorization of species, a quick explanation is that lower C-value species are more opportunistic plants that can generally thrive in very disturbed environments and higher C-value species are more tied to intact native communities. Another way to look at it is that higher C-value species are more vulnerable to habitat degradation. All species are ranked on a scale from zero to ten (the values I’m using are specifically for Nebraska) and all exotic species get an automatic zero.

In general, the restored prairie has the same grass species as the remnant, although many are less abundant. Most of those less abundant species will spread over time as the restored prairie continues to mature. A few sedges, including sun sedge, do not establish well from seed, and we're attempting to bring them in as transplants and let them spread from there.

The main difference in "weedy" forbs between the remnant and restoration is the abundance of goldenrods in the restoration. Canada and late goldenrod were both from the seedbank, but stiff goldenrod was planted by us. At this point, I'm not concerned about the goldenrods (they don't appear to be as aggressive here as in some places) because they haven't been decreasing species diversity over time.

As with other species, I expect many of the more conservative forbs species will increase over time in the restoration.

Based on experience, I'm sure Kentucky bluegrass and smooth brome will increase over time in the restoration, but so far we've been able to manage those species to keep them from overwhelming the plant diversity in other older restorations. Apart from those two species there are no serious invaders that in the restoration that might threaten the remnant, which is good to see.

It’s easy to find differences between the remnant and restored plant communities in this example – some plant species are much more abundant in one than the other. On the other hand, very few plant species from the remnant are missing completely from the restored prairie, and those that are less abundant are likely to increase over time. As a prairie ecologist, I can see some obvious visual differences between the restored and remnant prairies, but most visitors to our site see the two as one large prairie. But… Does any of this matter? How do I decide?

First, remember that the objective of this restoration project was NOT to replicate the remnant sand prairie, but to increase the viability of the species and communities living in it. Given that, the real questions I need to answer include the following: Does the restored prairie increase the population size of species formerly constrained by the small remnant prairie? Does the combination of the restored and remnant prairies provide suitable habitat for species that don’t occur in prairies the size of the remnant alone? Does the restored prairie add to the overall resilience or ecological function of the remnant prairie? Any questions about similarities or differences in the abundance of individual plant species need to be framed within the context of these kinds of broader questions – and tied to the specific objectives for the restoration project. Comparisons outside of that context are relatively meaningless.

To begin evaluating the impact of the restored prairie, one first step could be to look at a few at-risk species in the remnant prairie to see if the restoration appears to benefit them. If the remnant prairie has been harboring a small population of Franklin’s ground squirrels, for example, it’d be good to find squirrels (and their burrows) in the restored prairie as well. If there was a rare penstemon species in the remnant (bumblebee pollinated) it’d be interesting to follow bumblebees from the plants in the remnant to see if they also visit penstemon plants in the restored prairie – indicating that the restored prairie has facilitated growth of a genetically-interactive penstemon population.

Besides at-risk species, it would be worthwhile to search the restored prairie for the presence and/or abundance of species from other categories as well. These categories might include:

– Species that are representative of various types of relationships (e.g. predators and their prey, parasites/parasitoids and their hosts, insects and their larval host plants, etc.).

– Species that have a cascading effect on other species and ecological processes (e.g. allelopathic or parasitic plants, burrowing insects/animals, etc.).

– Species that are particularly important as food sources for a range of other species (e.g. springtails – aka Collembola, grasshoppers, “soft-bodied insects” like caterpillars and other similar larvae, etc.).

– Area-sensitive species that may not have been able to survive in the small remnant alone but that might have a chance in the combined restored/remnant prairie (e.g. prairie chickens, badgers, and other vertebrates).

It’s also important to evaluate impacts of the restoration project on groups of species that influence ecological processes – such as pollinators and seed dispersers. Pollinators are relatively easy to observe, and both the pollinators themselves and the resources they depend upon can be evaluated. Ideally, of course, it’d be great to have several years of data on the species richness and abundance of pollinating insects in a small remnant prior to initiating a restoration project, followed by similar data collection after the restoration has established. However, simply looking at whether or not purple prairie clover plants (for example) in the restored prairie are getting pollinated by the same species and numbers of pollinators as the prairie clover plants in the remnant could be very informative. From the resource perspective, if the remnant prairie tends to lack an abundance of flowering plants at a particular time of year (late spring, for example, or early fall), measuring whether or not the restored prairie provides appropriate blooming plant species to fill that gap is very important.

There are numerous other things that could be measured, including taxonomic groups we really don’t know much about at this point. For example, soil fauna, fungi, and obscure groups of invertebrates may very well have strong roles to play in ecological functioning of prairies, but we don’t know much about what those roles might be or how to evaluate them. While it’s certainly important to learn more about those other taxonomic groups, our lack of knowledge shouldn’t stop us from measuring what we do know in the meantime.

The last thing to consider is whether or not a restored prairie could be actually be negatively impacting the adjacent remnant prairie or its species. One example of this could be an invasive species that becomes established in the restored prairie – thus threatening the remnant. A second possibility is that the restoration could function as an “ecological sink” for some species from the remnant, in which a species is drawn out of suitable habitat into attractive-looking but perilous habitat instead. We’ve actually been testing for one possible example of this in our Platte River Prairies. Regal fritillary larvae feed only on violets, but adults don’t lay their eggs directly on violet plants. Our lowland remnant prairies have lots of violets, but our restored prairies have very few (so far) because we are unable to harvest large numbers of seeds. We’re trying to make sure fritillaries aren’t laying eggs in the restorations where the larvae would be doomed to starve because of the near absence of violets. (So far it looks like it’s not a big problem.)

As I mentioned at the beginning, we’re just starting think about how to measure the effectiveness of restored prairies as conservation tools. Since the initial practical work of a prairie restoration project involves the establishment of a new plant community, it’s natural to assess the success of the various species we included in the seed mixture. Unfortunately, it’s also easy to overemphasize the importance of floristic differences between a restored prairie plant community and nearby remnant prairies. For many reasons, it’s not practical to recreate a historic prairie or replicate an existing remnant prairie. However, it is possible to use prairie restoration to increase the viability of our remaining remnant prairies. It is imperative to set clear objectives for this kind of restoration work, including the specific ways we want the restored prairie to help abate threats to species and communities. Clear objectives will lead to easier decisions about how to measure success.

Many of the suggestions here are just first steps, and they and subsequent steps will require considerable resources, as well as collaboration with academic researchers. Yes, there’s a lot to measure, but as we start to establish consistent patterns of success with some kinds of species or ecological processes, we can start focusing attention more narrowly on others. We don’t have to test everything at once, and the most important measures at each site are those that evaluate whether or not specific objectives for that restoration project are being met. However, it will be critical that we all share what we learn – successes and failures alike – to build up our cumulative knowledge as quickly as possible.

There are a number of examples of restoration projects where remnants have been enlarged or reconnected by restoring adjacent lands. We should look closely at those existing sites to see if we can find evidence of success or failure (based on some of the suggested strategies above – and others). That knowledge can guide us as we plan and implement new projects in the coming years. It’s unlikely that we’ll be able to design restoration projects to benefit every prairie species and function, but we can certainly do a lot of good. There’s a lot of work to be done, but I’m very optimistic about our ability to make a real difference.