Earlier this month, I wrote about a project I’m undertaking this year to illustrate what we see happening in prairies that enter their first year of growth following a long period of intense grazing. The ways prairie plants and animals respond after that kind of grazing are some of the most fun and fascinating interactions I see in grasslands.

You can read the full background of the project in my previous post, but the basic idea is that I want to show people what happens in our plant communities when the dominant plants have been suppressed by grazing. In our case, I’m talking about grazing that keeps the prairie cropped short for most of a growing season, if not longer.

What we’re doing is very different, by the way, than the kind of rotational grazing approaches used by most ranchers. That’s not to say those rotational approaches are wrong. I just want to clarify the difference. We are using stocking rates that match or exceed what a rancher might use on the same land, but the goal of our experiments is to see how much habitat heterogeneity we can create.

Habitat heterogeneity has been strongly tied (through many research efforts) to both biodiversity and ecological resilience, which are our ultimate goals. We’re trying to learn as much as we can so we can help translate any lessons to ranchers and others who are looking to tweak what they’re doing to improve wildlife habitat, plant diversity, pollinator abundance, etc. We’re not to trying to talk them into doing exactly what we’re doing.

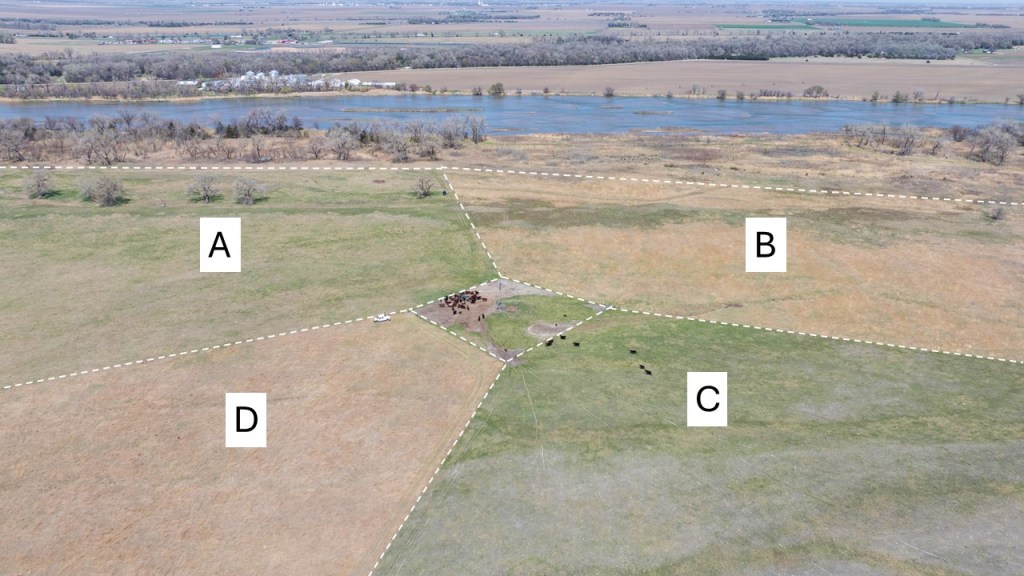

In my first post, I introduced two of the three sites I’m photographing this year. Today, I’m showing you the third. If you’ve visited our Platte River Prairies for a tour within the last several years, there’s a good chance you’ve seen this site up close. It’s the East Dahms pasture, where we’ve been testing open gate rotational grazing since for about six or seven years.

The site includes both remnant (unplowed) and restored (former cropland) prairie. The 80×80 foot plot I’m watching this year is in a 1995 planting done by Prairie Plains Resource Institute, which included about 150 plant species in the seed mix. It, and the rest of East Dahms, was managed with patch-burn grazing from about 2001 through 2018. We then switched to the open gate approach. As a result, it has gone through many cycles of season-long intense grazing, followed by long rest periods.

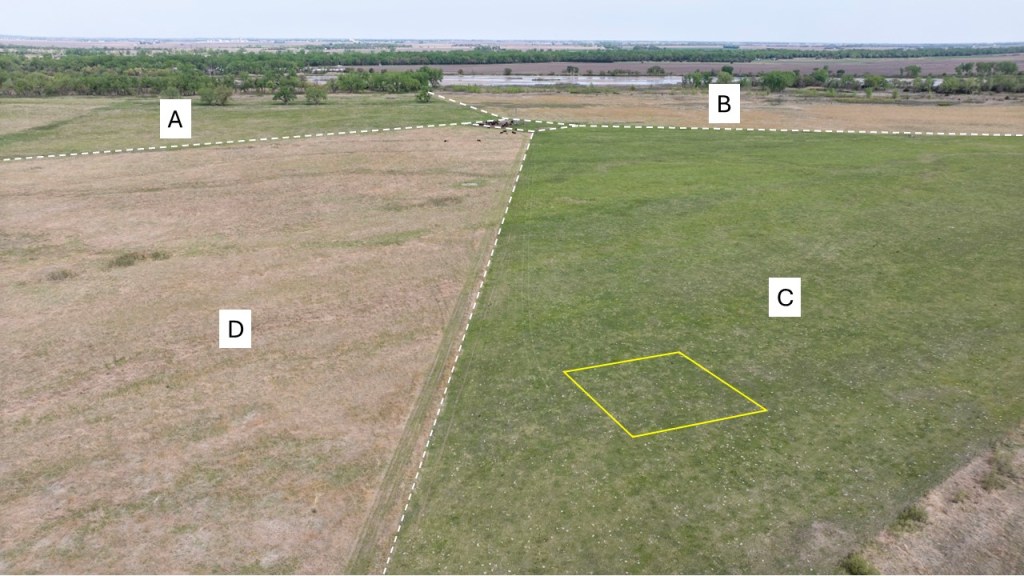

In the open gate rotational system we’re testing at this site, each pasture gets about a season and a half of grazing before going into a 2 1/2 year rest cycle. In the case of Pasture C (seen above), it was grazed from early July through October in 2023 and then from late May through October in 2024. By mid summer of 2024, the vegetation was nearly uniformly short and it stayed that way through the end of the 2024 season. This spring, cattle were put in the pasture around April 15 and pulled out last week, giving them one more chance to graze Kentucky bluegrass, smooth brome, and tall fescue (invasive grasses) before the pasture starts its long rest cycle. Pasture C probably won’t be grazed again until mid summer of 2027.

The two photos above show Pastures C (top) and D (bottom) with a spade to help show the vegetative structure. Both pastures were open to the cattle at the time, but the cattle chose to spend most of their time in Pasture C, even though it looks like there’s very little grass there. The quality of the fresh growth was apparently high enough to make that worthwhile. They wandered through Pasture D a little, mostly grazing smooth brome patches, but otherwise camped out in C until we closed the gate and they only had access to Pasture D.

The point of all that blathering is that this is a restored prairie, planted in 1995, that is just coming out of a long period of hard grazing. It should put on a good show this season, displaying the resilience of a diverse plant community and the animals (and other organisms) that are tied to those plants. As per usual, the big party is starting with a flush of annuals, biennials, and other short-lived plants.

Dandelions, annual sunflowers, and black medic are examples of the kinds of opportunistic plants that are taking advantage of both the bare soil and suppressed vigor of the normally-dominant grasses and other perennials in the prairie. Repeated grazing for many months hasn’t killed any of those perennials, but it has sapped them of a lot of their resources. They won’t grow very tall this year, and will be much less competitive, both above and belowground. By the end of next year (2026), however, they should be back to full strength.

Annual mustards are often abundant in these kinds of post-grazing situations, and they’re peppered throughout my plot this year as well. I’ve included photos of three species below (I’m 85% confident in my species identification – mustards are tricky for me).

Opportunistic plants include both native and non-native species, but there are none at this site (or the other two I’m tracking this year) that are categorized as invasive. They’ll all fade into the background by next year, as the dominant plants. We’ll see very few of them until the grazing cycle comes back around again to open up space for them.

Not all of the opportunists are annuals, either. Some, like hoary vervain, yarrow, and black-eyed Susans are perennial plants that can be relatively short-lived and come and go quickly in a plant community, depending upon the degree of competition from other plants. Either that, or they often survive the tough years (when dominant grasses are strong) as small, non-flowering individuals – just hanging on to life until their next chance to flourish.

It’s pretty easy for me to photograph the flowers in these post-grazing plots. I’ll do a lot of that this season and it’ll be fun to see the abundant color and texture they provide within the plant community, especially when we get into mid-summer when many of the bigger, showier species will start blooming.

However, the wildlife habitat values of the post-grazing party period are also important, so I’ll try to document those as well. Because the growth of most grasses will be limited this year, but opportunistic forbs will grow tall, the structure across these sites is likely to resemble a miniature savannah – with forbs instead of trees. Animals will be able to move easily through the short grass, but will have overhead cover for both shade and protection from predators. Insect abundance is typically very high under those conditions, too, including pollinators, herbivores, predators, etc.

Here are a few invertebrate photos I took a few days ago in the East Dahms plot.

Right now, these three plots might look pretty rough/ugly, depending upon your perspective. The vegetation is very short and there’s a lot of bare ground exposed. That runs counter to what most ranchers are taught about range management. It is also very difficult for many prairie folks to look at because it looks the same as many chronically overgrazed pastures they’ve seen.

The crucial difference is that these sites are being given plenty of opportunities to rest between grazing bouts, so we’re not losing perennial plant species – even those that cattle really like to eat (e.g., common milkweed, Canada milkvetch, entire-leaf rosinweed, prairie clovers, etc.). Our prairies look very different from year to year, but all the constituent plant species seem to handle the dynamic conditions just fine – while we also create a wide variety of habitats to support a diverse community of animals. At the East Dahms site, we’re also tracking what’s happening in the soil and I’ll share those results when I can (the news is good so far).

Anyway, stay tuned. It should be a fun year, even if our current drought conditions hang around and/or intensify. No matter what the weather brings, there will be a lot happening at the party.