Quick announcement: if you’re a graduate student doing research related to conservation in the Great Plains of North America, you should check out the J.E. Weaver Competitive Grant Program. We are offering up to five grants of $1,500 each to graduate students. Read more here.

About a week ago, I posted a bunch of nerdy graphs with data from some of our restored sites at the Platte River Prairies. I’ve been glad to hear from at least some of you that found those interesting. However, graphs showing how species richness or individual species occurrence changes over time are interesting, but they only show parts of the overall story. I’ve been playing with another way to better illustrate the full picture of a plant community’s species composition through time.

What I really want to do is to step back and look at an entire plant community to examine how its composition changes through time. The concept I’m sharing today has been useful to me, but I’d love to hear feedback from others. I’d also like help naming the graphics I’ve constructed. When I started, I called them plant community signatures, but that’s doesn’t feel quite right. Help?

(For those of you who are more interested in pretty pictures than data, I did throw in a few recent photos of ice bubbles at the very end of today’s post, just for fun. If you want to see them, however, you’ll have to scroll past all my cool visual data representations first.)

The data used to create these illustrations are the same data I showed graphs of in my last data post. As a reminder, to collect the data, I plop down a 1x1m plot frame, list the plant species within it, and then repeat that over and over across a site (about 70 or more times per site). I can then calculate frequency of occurrence for each species, which is simply the percentage of those 70 or so samples each species was found in.

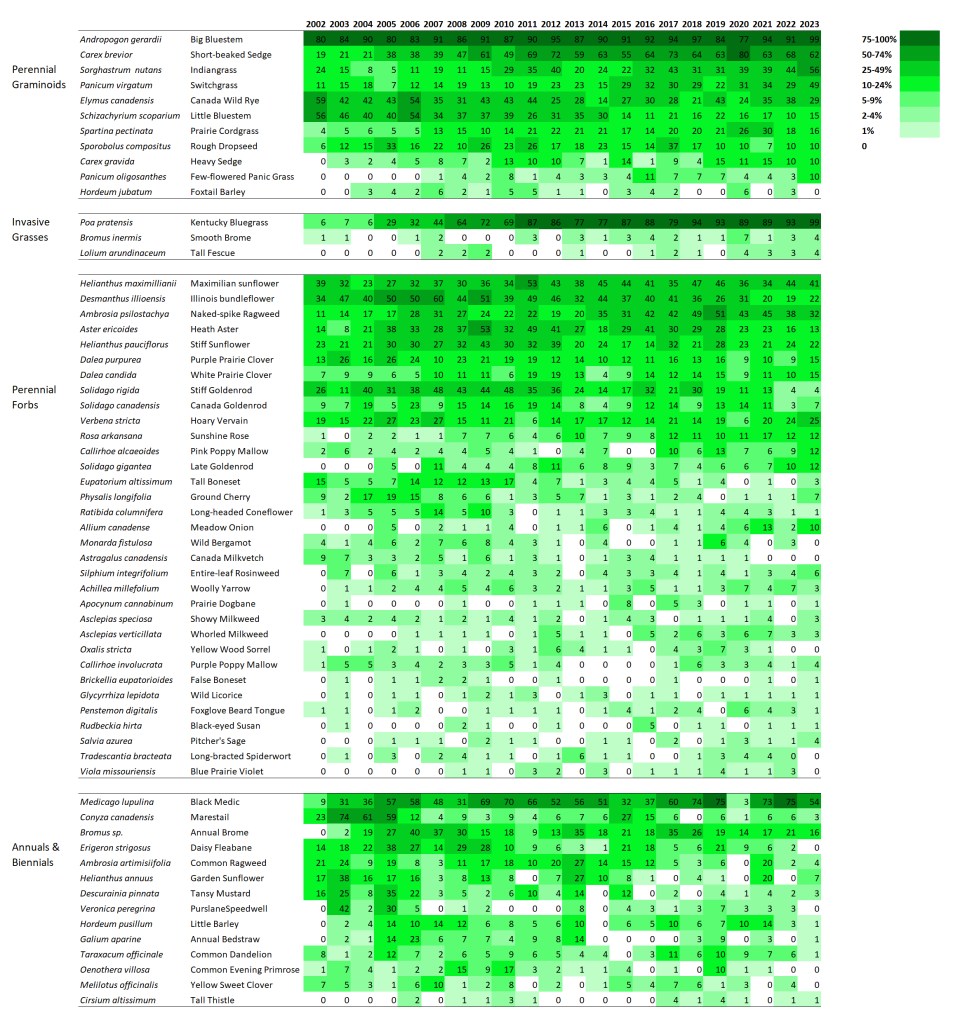

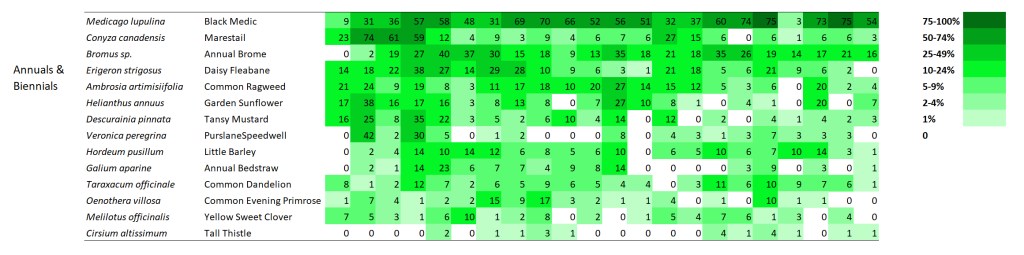

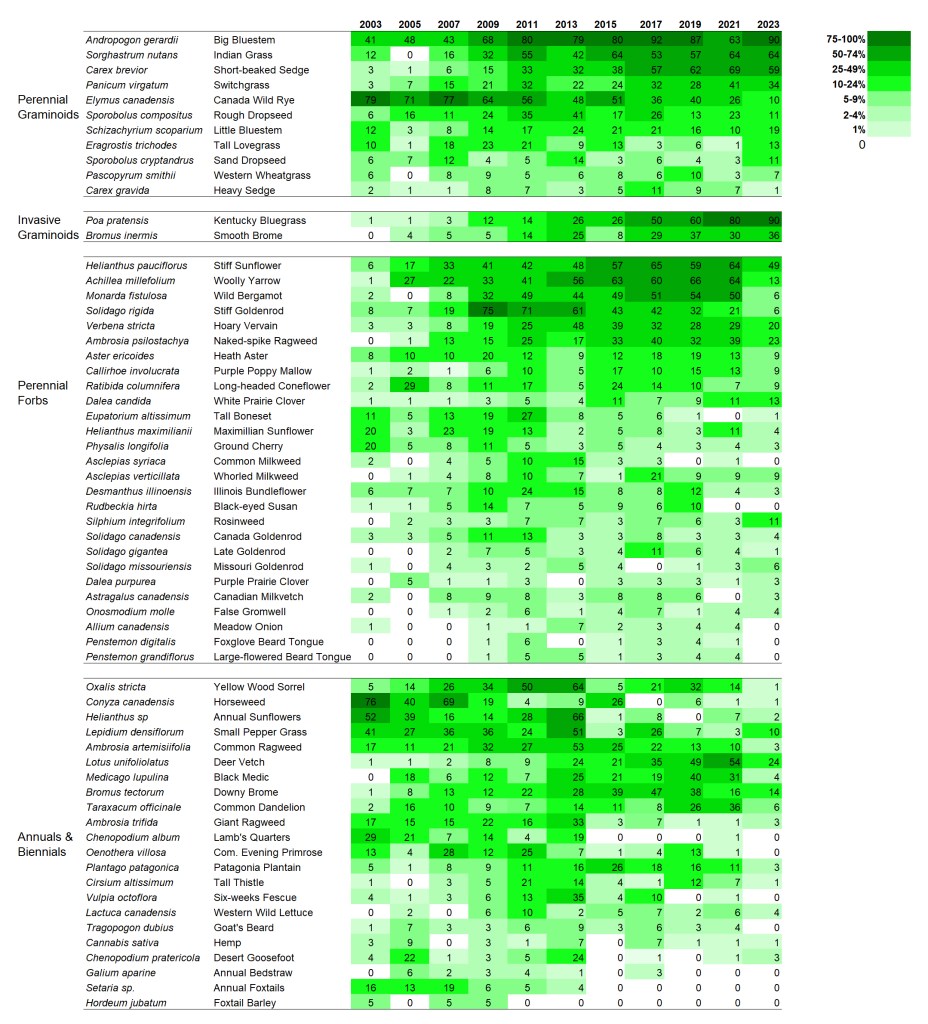

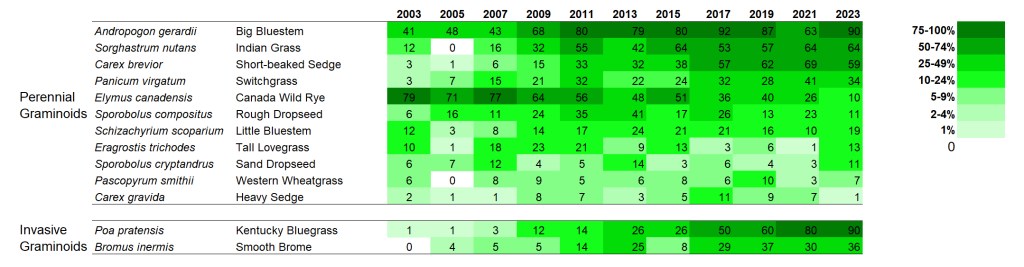

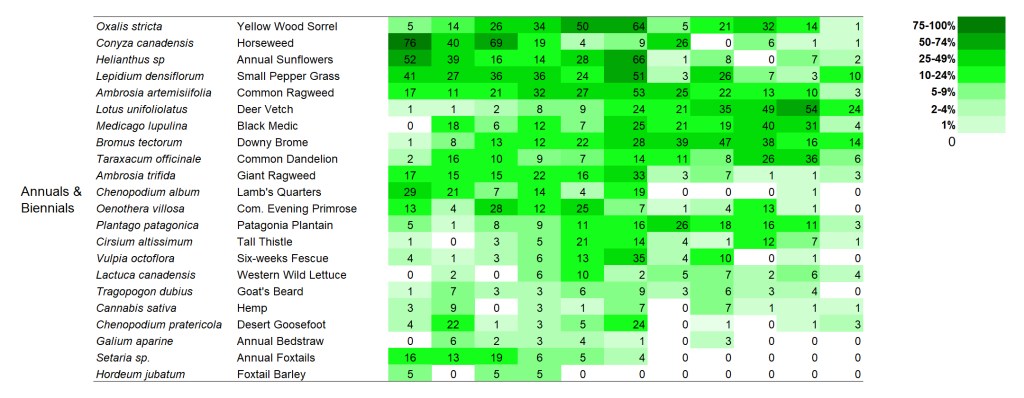

Once I have the data, I lay it out in a spreadsheet format to display the frequency of occurrence changes for each species through time. However, to make it easier to see patterns, I’ve colored each cell so that less frequent occurrence is light green and more frequent occurrence is dark green. I’ve also tried to group species together in a logical way. The result – at least to me – is a fascinating way to step back and study how plant composition varies over time.

I’m displaying results for two sites here. The first is a 1995 planting that I’ve collected data from annually since 2002. The second is a 2000 planting that I’ve collected data from every other year since 2003. I’m not displaying results for every species – just 60 or so of the species in each site that are abundant enough to be captured fairly regularly in 70 1x1m plots. If you want more details on these sites, you can get it from my last data-heavy post.

SITE 1 – Dahms 1995 Prairie Restoration. A 45 acre mesic site on sandy loam soils planted in spring of 1995 with approximately 150 plant species.

Remember to click on the title to open this post online if you’re reading it in an email. Doing that will then allow you to click on each image to see a larger, more clear version of it.

When I stare at this graphic, the first thing I notice is that there are very few examples of species that are on a distinct trajectory of increasing or decreasing frequency of occurrence. Most species simply fluctuate up and down through the years – some more dramatically than others. As expected, most of the most variable species are in the ‘annuals and biennials’ category. I think that’s great, and is evidence of ecological resilience.

Now, let’s look more closely at each of the four categories.

Looking at the perennial grasses, it’s clear that big bluestem has been a dominant feature of this site for the duration. That’s fine, but not particularly surprising to me. What’s more interesting is the increasing abundance over time of both short-beaked sedge and Kentucky bluegrass. I’m happy about the sedge becoming more common. It’s a cool little plant. Kentucky bluegrass, of course, is less exciting because it has the potential to form monocultures and decrease plant diversity.

However, and this is really important, I’m not seeing any evidence – either here, in my other analyses, or on the ground, that Kentucky bluegrass is having a significant impact on plant diversity. Now, that could certainly change, but at least so far, it seems to be just hanging out (though it’s hanging out in a lot more places than it used to). It’s a great reminder that we should always measure the impact of invasive species, rather than just measuring the extent or abundance of the invaders themselves.

I’ll quickly highlight two other species that intrigue me. Little bluestem has become less common across the site over time, though it seems to have stabilized at about 10-20% occurrence in recent years. Simultaneously, prairie cordgrass has done the opposite, becoming more common.

Little bluestem likes drier habitats and cordgrass likes wetter. Does that mean the site has gotten wetter? I don’t think so. Instead, I think what we’re seeing is a long-term self-sorting process of a planted prairie. When the site was planted, the seed mix included way more little bluestem seed than cordgrass seed. As a result, I think the early establishment of those two species wasn’t representative of their actual adaptation to the site. Over time, I think they’ve both shifted around until they’ve settled into the microsites (and abundances) they’re best suited to.

I don’t see much drama happening within the perennial forbs at this site. That’s pretty reassuring, actually, given the kinds of stresses that the prairie has experienced. It’s been managed with patch-burn grazing or open gate grazing since 2002, when this data collection started. As a result, the plant community has been exposed to fire, season-long intensive grazing, and multi-year rest/recovery periods. On top of that, of course, are the wet and dry years that can also significantly affect the growth and survival of plants. It’s good to see that none of these species seems to be disappearing (which also matches up with my other analyses of our restored prairies).

The only species I see that seems to show a significant trend toward lower abundance is tall boneset. That’s not a species known to be particularly sensitive to grazing pressure, as far as I know. In fact, I think of it more as a plant that does well with the kind of lower grass dominance that comes after a bout of grazing.

My best guess is that tall boneset is a species that started out very abundant because of both lots of seed in the mix and a slow, weedy early establishment period for this planting. Over time, it might just be dropping in abundance because it’s not as competitive in this soil type when competition from its neighbors is stronger. I’m just guessing here, though. The point is that the graphic helps me identify this pattern and ask questions!

Within the annual and biennial plants I included, it’s fascinating to see how volatile their frequency of occurrence can be from year to year. I don’t see any species with a decided trend – the species seem to just bounce up and down. What’s most intriguing to me is that all the bouncing doesn’t seem to be synchronized across species. In other words, all these short-lived plants are responding to different stimuli as they increase and decrease in their abundance.

SITE 2 – Dahms 2000 Prairie Restoration. A 69 acre mesic prairie on sandy loam soils planted over the winter between 1999 and 2000.

Now, let’s look at the second site (the one shown in the photo at the beginning of this post).

I’ve only collected data from the Dahms 2000 site every other year, so there are fewer columns. Also, the site was only in its fourth growing season when I started collecting data, so we’re seeing more of the ‘early establishment’ phase of this site than we did of the 1995 planting, which was in its 8th year of growth when I first collected data there.

Interestingly, there is a little more directional change within the grasses at this site than in the 1995 planting. Is that because the data includes earlier periods? Maybe, but even so, the change seems to continue past the first 8-10 years for at least some species. Big bluestem, Indiangrass, short-beaked sedge, and switchgrass all seem to be on trends of increasing frequency. Canada wildrye seems to be going in the opposite direction so it’ll be interesting to see if/where it levels off.

Both Kentucky bluegrass and smooth brome have increased in percent frequency over time. However, as in the 1995 planting, I’m not seeing any negative impacts on species diversity (yet?).

Within the perennial forbs, a few species at the top (stiff sunflower, yarrow, and bergamot) seem to be on an upward trend, at least before the last sampling period. You might notice that there are a lot of species – across all the categories – that dipped in frequency in 2023. I’m pretty sure that’s a consequence of thatchiness caused by a recent lack of fire and grazing, which was intentional on the part of the Platte River Prairies preserve manager (a combination of a scheduled rest period and a response to a couple dry years). I’m confident the numbers will bounce back up again over the next few years as the site gets more fire and grazing again.

Apart from those species, I think the most interesting thing about the perennial forbs is the lack of many obvious trajectories. For the most part, species seem fairly stable in their abundance through time, though some ebb and flow in interesting ways. Some species that have been labeled ‘aggressive’ in some circumstances don’t seem to be acting that way here, including Canada goldenrod and Maximilian sunflower.

Just as in the first site, short-lived plants bounce around a lot in their frequency of occurrence. The variation over time is evident even though the data was only collected every two years. Once again, I don’t see much synchrony within those bounces, which tells me each species responds individually to the myriad stresses applied to the site over time. Fascinating!

So, there’s my attempt at a visual display of plant community change in our restored prairies. Does the approach seem helpful? Suggestions for improvement? Ideas for what to name the graphics?

.

And now, for those of you hoping to see pretty pictures, here are three photos of ice bubbles from a restored wetland at the Platte River Prairies last week. Enjoy!