Last Friday night, I had the honor to be part of an event called the Conservation Jam, hosted by The Center for Great Plains Studies and The Nature Conservancy, and attended by about 300 people. I was one of 15 conservationists asked to present a “big idea” to help conserve the Great Plains. There was just one catch – each of us had to give our presentation in three minutes.

Three minutes is not very long.

I thought I’d share my presentation with you. Partly because I spent a lot of time putting it together and only got to spend three minutes presenting it. (But mostly because I’m too lazy to come up with another idea for a blog post this week.) The topic of my presentation was not a new idea; if you’ve followed this blog, you’ve seen more extensive posts on similar subjects twice before, in January 2011 and February 2012. The change of focus I advocate for isn’t, by itself, going to save the Great Plains, but I do think it’s a very important part of our approach going forward.

For what it’s worth, here’s my three minute presentation:

In grasslands, the vast majority of species are plants and invertebrates. Birds and other vertebrates make up a very small proportion of those species.

.

Between them, plants and invertebrates drive the ecological function of prairies (including pollination and soil productivity; and they are the food sources for most creatures). In other words, they’re what make grasslands tick.

.

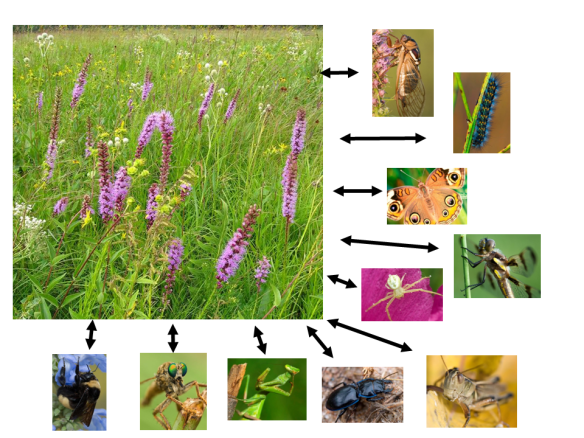

The diversity of plants influences the diversity of invertebrates, and vice versa. That complexity is the foundation of the resilience and overall stability of the ecosystem. It’s critically important to maintain plant and invertebrate diversity because without it, the ecosystem breaks down.

.

So clearly, as grassland managers and advocates for prairie conservation, we spend the vast majority of our time focusing on plants and invertebrates. …Right?

.

Wrong. We actually focus mostly on birds. Birds we shoot and birds we watch. I really like birds, but they’re not good indicators of how plant and invertebrate communities are doing, so they don’t tell us much about prairie function. Birds are an important part of conservation, but they’re only a small piece – we need to be sure our focus on them doesn’t distract us from the broader ecosystems they live in.

.

A couple years ago, we brought these Illinois botanists to Nebraska to help us with a research project. We had to, because there aren’t many people in Nebraska who can identify the majority of plants in a prairie. That’s embarrassing. More importantly, how can we manage prairies or evaluate our conservation progress if we can’t identify the species we’re trying to conserve??

.

We know even less about insects and other invertebrates. Of the few entomologists we have in Nebraska, most focus on crop pests. As a result, we really don’t know what species of pollinators or other insects we have, let alone how they’re doing. This is Mike Arduser, who came up from Missouri last year to help us learn about bees on the Platte River.

.

Look, we have GOT to make some changes. We desperately need naturalists with broad bases of experience who can help us study and assess plants and invertebrates. We need to know what we have so we can see if we’re winning. It’s up to all of us to broaden our own focus, but also to encourage others to do the same.

.

Birds are beautiful, they’re worthy of conservation, and they’re great at attracting people to nature…

.

.

We need to create more opportunities to learn both insects and plants. More importantly, we need to convince people that plants and invertebrates are interesting enough to care about. There are resources like bugguide that can help amateurs like us identify insects, but they only work if we use them.

.