In our Platte River Prairies, regal fritillaries and other butterflies appear to depend heavily on a few weedy wildflower species as nectar plants.

I was in graduate school when I first started learning to identify butterflies. I participated in several July 4th butterfly counts around Nebraska, and got to know some people who could help me with the tougher-to-identify species. I was a good birder at the time, and quickly found many parallels between bird and butterfly identification. One of those was that skippers were just like sparrows – lots of small drab-colored species that were really difficult to tell apart. The difference, of course, was that I could catch skippers with my net to see them up close.

One species that wasn’t difficult to identify was the regal fritillary. Once I figured out how to tell the difference between regals and monarchs I started seeing regals everywhere. In fact, when I helped with July 4th counts, regal fritillaries were usually one of the most abundant species we saw. I didn’t realize until later how rare regals are in eastern prairie states, and how fortunate I am to live in Nebraska where their populations are still strong.

Regal fritillary butterflies are still common in many western tallgrass prairies and mixed grass prairies, but have largely disappeared from most eastern prairies.

As I learned more about the species and its conservation status, I saw some inconsistencies between what regals were thought to need for survival in eastern prairies and what our Platte River Prairies were providing. For example, many people I talked to from the east told me that regal fritillary larvae needed prairie violets for a food source. However, our Platte River Prairies – which are full of regal fritillaries – only have the heart-shaped-leaf blue violet (Viola pratincola), and no prairie violets. In addition, plant species like purple coneflowers (Echinacea spp) that are heavily used as nectar plants by regal fritillaries aren’t present in the floodplain of the Central Platte River. In 2010, with the help of Dr. Ray Moranz of Iowa State University, we started a research project to learn more about how regal fritillaries survive and thrive in our prairies.

Through the project, we’re investigating multiple aspects of regal fritillary habitat use – including nectar plant use, the use of remnant vs. reconstructed prairies, and the way in which regals interact with a landscape managed with a combination of fire and grazing. We’ve only completed one field season so far, and will need more time to answer those questions, but we have already seen some very striking results in terms of nectar plant use.

To collect our data, we regularly walked transects through our prairies and counted butterflies – noting nectaring behavior when we saw it, and recording the species of flowers the butterflies were nectaring on. I’m only referring to the nectaring data in this post because we’ve got more work to do to analyze the other data we collected. It’s also important to remember that these are just pilot-year data, although they match what I and others have observed for many years.

Though we saw many hundreds of regal fritillaries on our transects, relatively few were actually nectaring. Early in the season when numbers were highest, we saw mainly males – patrolling for newly emerging females. When those females finally arrived on the scene we started to see nectaring behavior from both males and females, but observations of nectaring were still relatively rare. Multiple years of data collection will be important to confirm the patterns we saw this first year.

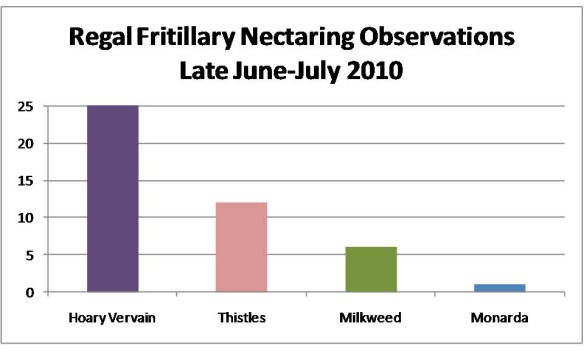

There were really only two kinds of wildflowers that attracted the vast majority of nectaring regal fritillaries through the 2010 season, and both are usually called weeds. The first was hoary vervain (Verbena stricta) and the second was a small group of thistle species – primarily Flodman’s thistle (Cirsium flodmanii) and tall thistle (Cirsium altissimum). Hoary vervain is a native wildflower that is largely considered to be a pasture weed by many people because it thrives in overgrazed situations. Cattle don’t like to eat it and it can spread quickly when the surrounding grasses are weakened. (However, it also decreases in abundance very quickly when the grasses regain their vigor.) Flodman’s and tall thistle are two native thistles that are also considered to be weedy plants, and that do well in overgrazed pastures. The third favorite plant was actually several species of milkweeds lumped together (primarily weedy species like Asclepias syriaca and A. speciosa).

During the early part of the summer, the majority of regal fritillaries nectaring on flowers chose hoary vervain.

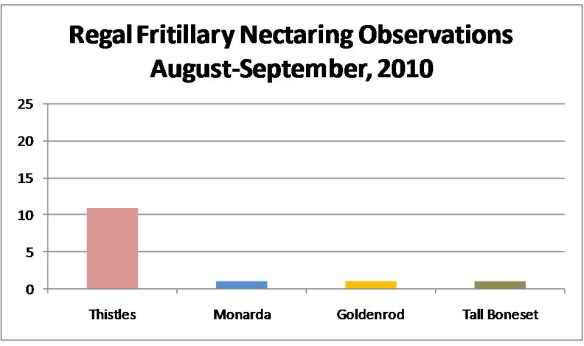

In late summer and early fall, vervain largely stopped blooming and other species became more important for nectaring, particularly native thistle species.

Most of our data collection centered on regal fritillaries, but we also collected data on other butterfly species. So far, there doesn’t appear to be much difference in the nectaring preferences of regals and the larger butterfly community. During the early part of the season, hoary vervain was the primary choice for most butterflies and a variety of other species got only infrequent visits. Later in the season when hoary vervain was largely done blooming, thistles and a few other species, including wild bergamot – aka monarda or Monarda fistulosa and rosinweed (Silphium integrifolium), shared the load.

Observations of early summer nectaring across all butterfly species showed that hoary vervain was the dominant selection for nectaring.

One of the most interesting aspects of doing this research on butterflies has been that I’ve been able to look at our prairies through the eyes of butterflies – and that’s given me some surprising insights. Our remnant prairies are largely degraded by years of overgrazing and broadcast herbicide use, and we’ve been working to slowly bring them back to higher floristic quality. I’ve assumed that increasing floristic quality would also be good for many other species, including butterflies. In addition, we’ve worked very hard at getting the highest plant diversity we can into our restored (reconstructed) prairies. While we’re not restoring those prairies for butterflies, specifically, I’ve always assumed that butterflies would benefit from high plant diversity. From our very preliminary data on butterflies, it appears that while our restored prairies have many more flower species, including many showy species, they may not be providing any better nectaring opportunities than our remnants! The flower species most used by regal fritillaries and other butterflies are hoary vervain and thistles, which are at least as common in our remnants as in our restorations.

Regal fritillaries, and other butterflies, seem to rely heavily on hoary vervain for nectar in our Platte River Prairies.

I’m confident that there many other benefits of the plant diversity in our restorations, of course, including the availability of a variety of larval host plants for butterflies. But it’s a little humbling – and intriguing – to see butterflies relying on plant species that do well in beat-up pastures rather than flocking to our showy restored prairies! It’s important, of course, not to extrapolate these results to other parts of the country. I’m not saying that regal fritillaries can survive in beat-up pastures in eastern states. If that was so, we’d have many places in the east with lots of regal fritillaries. Nebraska and other western states with high numbers of regal fritillaries also have landscapes with relatively high amounts of native prairie – and that may be the most important factor for regal fritillary survival.

The other lesson from our early data seems to be that the value of “weedy” species shouldn’t be discounted just because they thrive in conditions many flower species can’t take. Vervain and thistles could be the primary plant species supporting our butterfly populations along the Platte River right now. That’s a pretty good argument for being valuable. In addition, the violet species that the regals must be using as a larval food plant along the Platte is considered to be relatively weedy because it does well in degraded pastures. I’m sure glad we have a lot of it – and so are regal fritillaries! Other weedy plant species have value as well – apart from their obvious role in filling space when “good” plants are weakened by fire, grazing, or drought. The seeds of native ragweed and annual sunflower species, for example, seem to be excellent food sources for many small mammals and birds (judging from the density of tracks around the plants when it snows).

I’m really looking forward to next season’s butterfly transects. I enjoyed reacquainting myself with butterflies last summer, and it was good for me to look at our prairie work through a different lens. I’m sure we’ll learn more as we collect and analyze more data. In the meantime, we (and our butterflies) will continue to enjoy and appreciate our weeds.

A big thank you to Dr. Ray Moranz for his assistance setting up this project. Also, Mardell Jasnowski directed most of the data collection in 2010, with help from Nanette Whitten, Nelson Winkel, and Natalie Goergen.

I’ve always liked Verbena stricta, now I feel a sense of validation.

Glad I could help.

– Chris

Here in Central Georgia, all we have are remnant grasslands/meadows. Powerline cuts are great places to find weedy plant species…and butterflies. Gulf and Variegated Fritillaries are the dominant species at these sites. Both rely on Passiflora for their larval host plant.

Chris,

Love the article as I do all the ones that you post and love your book. Do you suppose the reason for the Regal’s and other butterflies choice of hoary vevain and thistle’s could be somewhat of an adaptation? Since there is little to select from in overgrazed pastures maybe the vervain and thistle are the only consistent “weeds” to feed upon. “Beggars can’t be chooser’s”, as they say. It would be interesting to see if Regal’s and other butterflies that fed in diverse prairies presented a more diverse food selection. Also, do you think there could be a correlation between established/reconstructued prairies nearby overgrazed pastures (which could be the case the further West you went like in the Sandhills) where lots of Regal’s are represented and that the established/reconstructed prairies serve as a host. This being said given the fact that the butterflies diet is solely vervain and thistles. Just some food for thought. Keep the posts coming!

Brandon, It’s a good question. I’m sure that if purple coneflower was here, regals would use it. What I’d really like to know is whether there is a nutritional difference between coneflower and vervain (or other plants). Is there a quality difference in nectar? Or a difference in amount of nectar obtained per unit effort?

Glad you like the blog and book.

Chris

Any sign of them using noxious (musk, Canada, etc.) thistle?

Jeff – yes, butterflies definitely like musk thistle in particular. We don’t have enough Canada thistle for me to have a good feel for that. For a while, the only good photos I had of regal fritillaries were on musk thistles… and no one wanted to use them!

One of the challenges we face is trying to eliminate noxious weeds without also eliminating their native counterparts. Most people don’t distinguish between native and non-native thistles. That’s why it’s so important to show them the value of those natives.

-Chris

Pingback: Tweets that mention The Importance of Weedy Flowers for Butterflies | The Prairie Ecologist -- Topsy.com

I’ve actually noticed this just in my 2,000 square foot garden herein Lincoln! How cool to see it here on a much larger scale. I don’t like vervain, boring, except for winter interest, but I have several clumps growing that bring in these butterflies. And I so wish people could differentiate between native and non thistles.

Vervain is probably an acquired taste. It’s actually very pretty, but it does have a “weedy” look to it. Not sure how to define that, exactly.

Thistles in Nebraska are actually really easy to differentiate. Of the 10 species we have, 5 are native. If they’ve got fine white hairs on the underside of the leaf they’re native (Flodman’s, wavy-leaf, tall, yellow-spine, and Platte). If they’re green on the bottom they’re not.

– Chris

Pingback: Butterfly Aggression | The Prairie Ecologist

Pingback: Regal Fritillary Butterflies in the Platte River Prairies – 2011 | The Prairie Ecologist

Pingback: Lessons From a Project to Improve Prairie Quality – Part 1: Patch-Burn Grazing, Plant Diversity, and Butterflies | The Prairie Ecologist

Has this work at all changed your attitudes towards non-native species, i.e., are you still actively seeking to eradicate musk thistles and other “butterfly-attractive” non-native thistles? Do any of these non-natives serve roles where there don’t seem to be any native counterpart that you can promote instead?

Peter – We are forced to eradicate (or at least make a good effort toward eradication) musk thistles because they are a noxious weed in Nebraska. So we do. But I’d rather not. Canada thistle is also noxious, but bull thistle is not (both are exotic). We generally don’t worry about bull thistle and allow it and native thistles to bloom as much as possible. In fact, we include the native thistles in our seed harvesting and try to get them in our new seedings.

I’m not sure I can identify any roles the non-natives are playing that aren’t covered by natives, though the abundance of non-natives can be higher than natives, in some cases (including thistles).

In general, I’m not very worried about whether something is non-native or native – more about whether it promotes biological diversity and resilience or not. We don’t include non-natives in our restoration seed mixtures, but I don’t spend time trying to control them unless they’re causing some kind of demonstrable harm that makes our time and energy to control them seem worthwhile.

I’m always impressed to see how people can share ideas toward being green at home.

I must admit though, I’d really like to see more focus on this being pushed in the corporate world. I know there are some efforts made by some corps, but just imagine if this was pushed as an everyday thing. After all, we spend the majority of our time at work and these habits would simply carry through.